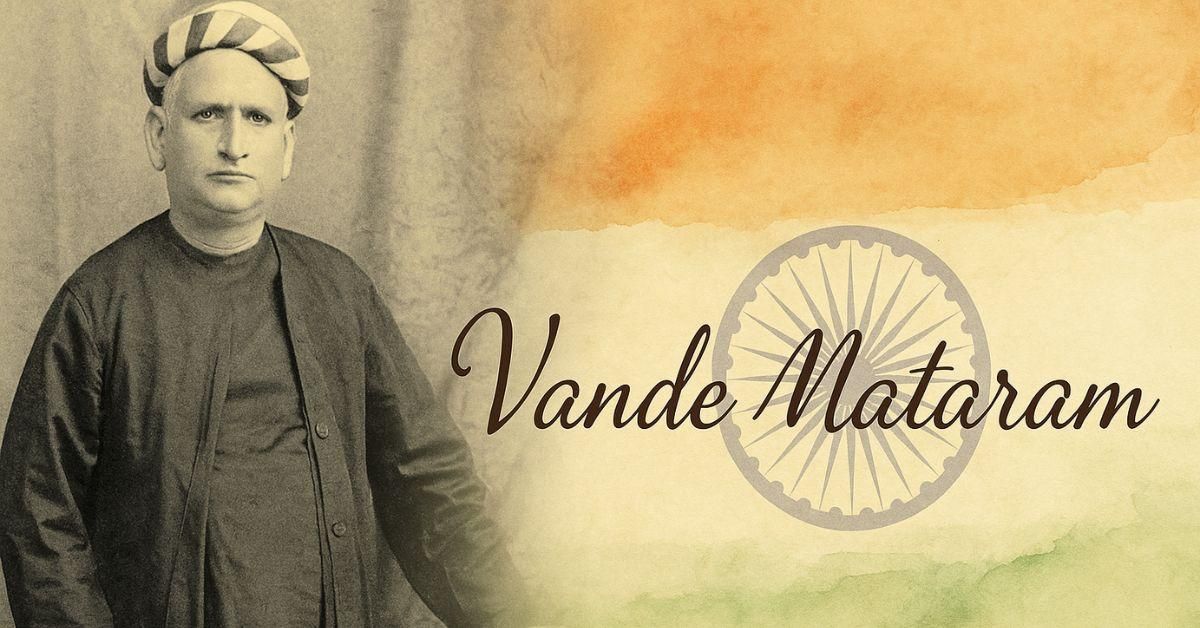

Last year, the same day, when I visited Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s birthplace in Naihati, I felt something far greater than historical nostalgia. The gentle Ganga breeze, the rustling banyan leaves, and the quiet pathways seemed to still carry the pulse of a revolution. It felt as if the winds themselves whispered the chant that once shook an empire: “Vande Mataram”, as a heartbeat of a nation, not as a mere slogan.

Today, as Vande Mataram completes 150 years, we are not celebrating just a song, we are bowing to the civilizational consciousness of Bharat, reawakened by Bankim Chandra in 1875, a hymn that turned ordinary people into freedom fighters.

The Song That Became a Nation’s Voice

Vande Mataram saw India not merely as land, but as a living Mother, embodiment of strength, beauty, prosperity and wisdom:

त्वं हि दुर्गा दशप्रहरणधारिणी

कमला कमलदलविहारिणीवाणी विद्यादायिनी।

नमामि त्वां नमामि कमलाम्अ

मलाम् अतुलां सुजलां सुफलां मातरम्॥

Thou art Durga, Lady and Queen,

With her hands that strike and her swords of sheen, Thou art Lakshmi lotus-throned,

And the Muse a hundred-toned. Pure and perfect without peer, Mother, lend thine ear.

Rich with thy hurrying streams, Bright with thy orchard gleams, Dark of hue, O candid-fair

In thy soul, with jewelled hair And thy glorious smile divine, Loveliest of all earthly lands,

Showering wealth from well-stored hands!

Mother, mother mine!

(Translation by Sri Aurobindo) Mother sweet, I bow to thee,

Mother great and free!

This is not poetry. It is matri-bhakti – devotion to the Mother.

From the Swadeshi movement to cells of revolutionaries, from village processions to underground presses, Vande Mataram became the war-cry of freedom. When Bengal was partitioned in 1905, the streets thundered with it. When the British banned it in 1906, lakhs still sang it while being lathi-charged and arrested. When Khudiram Bose went smiling to the gallows, his last words were Vande Mataram. When Matangini Hazra was shot, she fell chanting Vande Mataram. When Subhas Chandra Bose electrified crowds, the masses roared Vande Mataram in unison. When Madam Bhikaji Cama unfurled the first tricolour in Stuttgart, Vande Mataram shone at its centre.

This song did not follow the freedom movement, this song was the freedom movement.

Yet, when independence arrived, those entrusted with shaping free India betrayed the soul of its struggle.

The first wound came early, during the Vande Mataram movement in Bengal, Motilal Nehru ridiculed the young Swadeshi activists as “oily Bengali babus.” That was a contempt for grassroots nationalism, not just mockery.

His son, Jawaharlal Nehru, carried that discomfort further. By the late 1930s, as the Muslim League intensified objections to the song, Nehru and Congress chose appeasement over cultural truth. In 1937, the Congress Working Committee edited the song, only the first two stanzas were permitted; the rest were suppressed.

But the real blow came later, when India needed to choose its National Anthem.

There was intense debate in the Constituent Assembly. Leaders like Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, K.M. Munshi, and many others strongly favoured Vande Mataram. It had been the anthem of freedom, the marching cry of sacrifice, the emotional unity of the nation.

But Nehru opposed adopting Vande Mataram as the National Anthem. He offered various arguments that the song was “too long,” that “it invokes imagery that may offend some communities,” and finally, the most political excuse that it would not fit into Western-style band orchestration. Yet this was disproven scientifically by Master Krishnarao Phulambrikar, who demonstrated that the composition suited orchestral arrangement perfectly.

Despite this, Nehru pushed hard for Jana Gana Mana, arguing that it had already gained “international recognition.” What was not acknowledged was that this recognition stemmed from its having been sung at British receptions, including one in honour of Lord Curzon. And so, a song that united a nation was sidelined to avoid “hurting sentiments.”

The irony is bitter: The very song for which Indians faced bullets was deemed too dangerous to officially honour. And thus, Vande Mataram was assigned a secondary place – equal in sentiment, but not equal in status.

This hesitation soon hardened into Congress tradition. Sonia Gandhi refused to attend Vande Mataram’s centenary observance.

Rahul Gandhi publicly instructed that Vande Mataram be sung “in one line” due to “lack of time.”

The Madhya Pradesh Congress government suspended its daily recitation in the Secretariat.

SP MP Shafiqur Rahman Barq refused to recite it in Parliament. RJD leaders declared that followers of “one God” cannot sing it. Congress leaders remained silent every time!

But history does not freeze. A nation, when it remembers its Mother, rises again.

Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has finally restored the emotional dignity of Vande Mataram. Citizens’ movements, cultural bodies, schools, universities, and, most profoundly, even in Muslim-majority Kashmir, have now declared that Vande Mataram will be sung in schools.

Where separatism once tried to break the nation, the Mother’s name returns. This is not political. This is civilizational. This is healing.

As Vande Mataram enters its 150th year, India is finally moving toward the vision the song itself proclaims:

सुजलाम् सुफलाम् शस्य-श्यामलाम्

A land fertile, prosperous, abundant – confident in its identity.

Vande Mataram is not a song we sing. It is a truth we live.

It is the memory we return to.

It is the future we are walking toward.

And so today, once again, the voice rises – not from politics, not from compulsion, but from the soul.

वन्दे मातरम्। वन्दे मातरम्। वन्दे मातरम्।