In a world where globalisation is no longer the dominant economic philosophy, the India–United States Interim Trade Agreement of 2026 signals something far more significant than tariff adjustments. It reflects the emergence of a new form of economic engagement — strategic bilateralism — shaped by geopolitics, supply chain resilience, and regulatory sovereignty. Nowadays, Major economies are increasingly prioritizing their supply-chain resilience and “friend-shoring” over pure cost efficiency. Within this shifting geoeconomic environment, India and the United States have deepened strategic convergence across defense, digital technology, critical minerals, semiconductors, and clean energy.

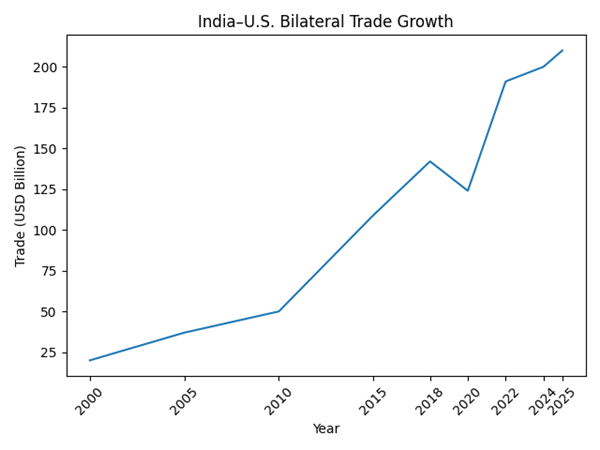

Historical trade trajectory

India–U.S. trade expanded from USD 20 billion in 2000 to over USD 210 billion by 2025, reflecting deepening economic integration and strategic alignment.

| Year | Trade (USD Billion) |

| 2000 | 20 |

| 2005 | 37 |

| 2010 | 50 |

| 2015 | 109 |

| 2018 | 142 |

| 2020 | 124 |

| 2022 | 191 |

| 2024 | 200 |

| 2025 | 210 |

Over the past quarter century, India–U.S. trade has expanded from just USD 20 billion in 2000 to over USD 210 billion in 2025. This tenfold increase is not accidental. It reflects a steady convergence of interests: trusted supply chains, democratic alignment, defence cooperation, and digital innovation. Even during the pandemic shock of 2020, bilateral trade demonstrated resilience, rebounding sharply to nearly USD 191 billion by 2022.

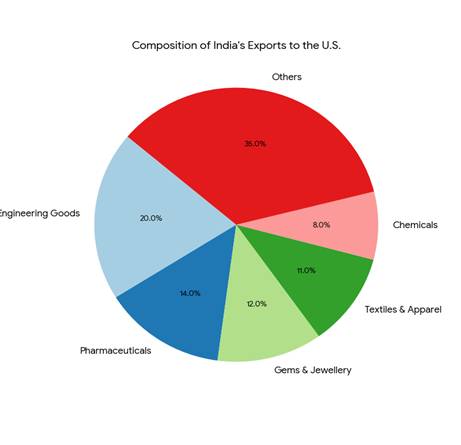

Today, Bilateral merchandise trade has expanded dramatically, making the United States India’s largest trading partner. India’s exports to the US are no longer confined to low-value segments but are diversified across pharmaceuticals, engineering goods, petroleum products, textiles, gems and jewellery, and a rapidly expanding digital services ecosystem. The structural depth of this relationship distinguishes it from earlier transactional trade ties. What once revolved around IT outsourcing and selective goods trade has now expanded into defence procurement, clean energy cooperation, semiconductor dialogues, and critical technology partnerships.

The global trading system is undergoing structural transformation. Multilateral mechanisms are weakened, tariff reciprocity has re-emerged, and technology has become inseparable from national security. In this context, the Interim Trade Agreement is calibrated rather than sweeping—and that is precisely its strength. Therefore, the 2026 Interim Trade Agreement must be interpreted not merely as a tariff adjustment framework but as a strategic economic instrument aligned with broader Indo-Pacific cooperation.

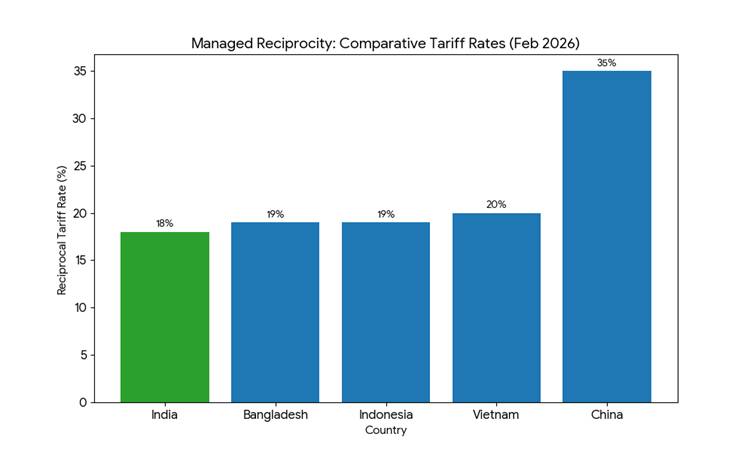

Reports indicate reciprocal tariff alignment around 18% for India, slightly more favourable compared to certain regional competitors. Sectoral advantages include zero-duty access for pharmaceuticals and gems and jewellery. In textiles and garments, duty-free provisions linked to the use of U.S. cotton reflect targeted reciprocity.

| Feature | India–U.S. Agreement (ITA) | Bangladesh–U.S. Deal |

| Reciprocal Tariff | 18% (Lower/Better) | 19% |

| Garment Access | Zero-duty (if using U.S. cotton) | Zero-duty (if using U.S. cotton) |

| Strategic Purchase | Proposed $500 Billion (Energy/Tech/Coal) | Primarily Aircraft/Cotton |

| Key Advantage | Zero-duty on Pharma & Gems | Reliance on U.S. Cotton inputs |

| Technology | GPU & Data Center Cooperation | Minimal tech alignment |

There has also been discussion of substantially expanding bilateral trade volumes over the coming decade. However, it is important to clarify that the widely cited $500 billion figure represents an indicative or proposed trade expansion aspiration under discussion—not a confirmed purchase commitment. In this context, India has positioned itself as a credible alternative manufacturing hub with scale, demographic depth, institutional capacity, and geopolitical alignment with Western economies.

India’s export basket to the United States reflects both diversification and upgrading. Pharmaceuticals constitute a critical pillar, with India supplying a significant share of generic medicines consumed in the US healthcare system. Engineering goods and machinery exports reflect deeper integration into manufacturing value chains. Gems and jewellery remain labour-intensive export segments sensitive to US consumer demand cycles.

Textiles and apparel continue to be important, though increasingly challenged by regional competitors. However, the strategic landscape has become even more complex with the United States simultaneously deepening economic engagement with Bangladesh. Bangladesh has emerged over the past decade as one of the world’s leading garment exporters, with a highly specialized apparel manufacturing ecosystem integrated into Western retail supply chains. Competitive labour costs, strong scale efficiencies, and extensive compliance reforms have enabled Bangladesh to capture significant market share in US apparel imports.

Therefore, the contrast between India and Bangladesh in the US market is structurally revealing. India’s exports to the US are diversified across high-value and knowledge-intensive sectors, whereas Bangladesh’s exports are heavily concentrated in ready-made garments. Bangladesh’s cost advantage in labour-intensive manufacturing remains substantial. For India, the challenge lies not in competing across all sectors but in defending and expanding its position in textiles and apparel where direct competition exists.

The competitive implications of US–Bangladesh engagement for India are therefore sector-specific rather than systemic. However, in apparel and labour-intensive manufacturing, Bangladesh’s cost competitiveness and export specialization create tangible pressure. India, as a Quad partner and a central pillar of Indo-Pacific strategy, occupies a fundamentally different strategic category in Washington’s calculus.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the evolving India–US trade architecture offers both opportunities and risks. On the opportunity side, supply chain diversification away from China creates openings in electronics, auto components, pharmaceuticals, renewable energy equipment, and defence manufacturing. Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes and industrial corridor development enhance India’s attractiveness to global manufacturers seeking stable and geopolitically aligned production bases.

On the risk side, sectoral competitiveness gaps—particularly in labour-intensive manufacturing—remain a constraint. India’s logistics costs remain higher than many competing economies. Labour regulation complexities, fragmented supply chains in textiles, and infrastructure bottlenecks can erode cost competitiveness. While Bangladesh’s LDC graduation in the coming years may alter its preferential trade status in some markets, its entrenched position in apparel supply chains ensures that competitive dynamics will persist.

The evolution of global trade governance further reinforces the importance of strategic bilateralism. The India–US economic corridor thus represents more than a bilateral trade relationship; it embodies a structural alignment within a shifting global order. India competes with Bangladesh in garments. It competes with China in technology and scale manufacturing. It partners with the United States in strategy, defence, and digital governance. These multiple layers coexist simultaneously. The challenge for policymakers is to ensure that sectoral competition does not obscure strategic complementarity.

Looking ahead, the trajectory of India–US trade will depend on three interlinked variables: domestic reform momentum in India, US political continuity in trade policy, and the pace of supply chain realignment away from China. At the same time, India must respond proactively to Bangladesh’s competitive rise in apparel by accelerating industrial modernization rather than relying on defensive measures.

Ultimately, the India–US trade reset unfolding today reflects a deeper transformation in global commerce. Trade is no longer about tariff arithmetic alone; it is about resilience, trust, geopolitical alignment, and technological capacity. If reforms keep pace with opportunity, the India–US economic corridor will not only withstand competitive pressures from regional players but will emerge as one of the defining trade relationships of the Indo-Pacific century.

Conclusion

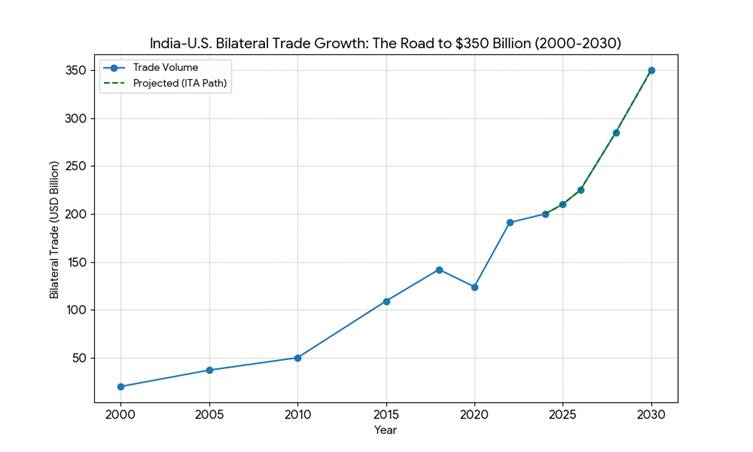

The India–U.S. Interim Trade Agreement (2026) represents a calibrated transition toward strategic bilateralism in an era of global economic fragmentation. Rather than a conventional tariff-liberalization instrument, it serves as a structural bridge toward comprehensive economic alignment. If institutionalized into a full Bilateral Trade Agreement, bilateral trade could expand to USD 320–350 billion by 2030

Author Dr. Bhavana Rai is an Economist. She is a regular contributor on public and academic platforms as a subject expert and economist, including Akashvani, Sansad TV, Bharat TV, and leading academic institutions such as Amity University and Jaipuria Institute of Management.