On Vijayadashmi Day, October 2, 2025, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh marked its hundredth anniversary. From Nagpur to New Delhi, from small village maidans to sprawling city grounds, swayamsevaks observed this historic occasion. As the saffron flag was unfurled, a single prayer rose in unison — “Namaste Sada Vatsale Matrubhumi.” It was the same hymn first sung a century ago, now carrying the weight of a hundred years of service and sacrifice.

At first hearing, it is simply a prayer to the Motherland. But for swayamsevaks, it is a covenant — an oath that every breath and every ounce of strength is to be given to Bharat. That oath has shaped a century-long journey: sometimes visible in uniforms at morning shakhas, sometimes invisible in the ruins of a flood-hit village or the trenches of a forgotten war.

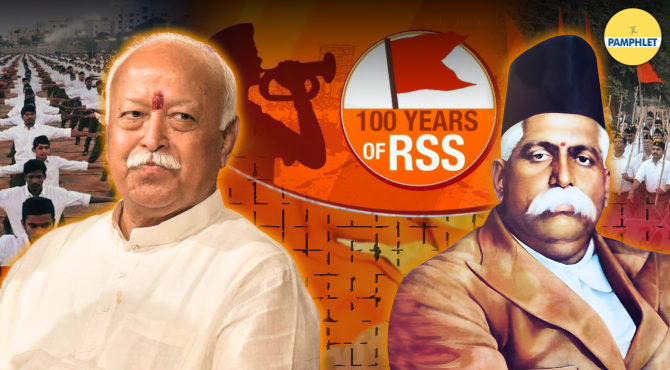

The birth of a nationalist organisation

In 1925, Nagpur was not just another provincial town. It was a crucible of unrest. India was still shackled by colonial rule, but the deeper fractures were internal — caste hierarchies, sectarian divides, and a fragile sense of national unity.

Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar saw that without character, there could be no freedom worth keeping. His answer was not a political party, but an organization built on silent discipline. A handful of young men assembled in an open ground, saluted a saffron flag, and drilled in unison. It was unremarkable at first glance — yet Hedgewar believed that if individuals could be molded, society could be rebuilt, and a nation could rise.

A century later, the image remains the same: the lathi, the prayer, the saffron flag — but the scale has transformed. From one shakha in Nagpur to tens of thousands across the globe, the Sangh has become one of the largest voluntary networks in human history.

Service without slogans

If the shakha was RSS’s tool of character-building, its true test was service. And it was tested often.

When the Andhra cyclone of 1977 flattened villages, swayamsevaks were among the first in the waters, ferrying stranded families and distributing clothes and utensils to thousands.

When the Gujarat earthquake of 2001 turned cities into rubble, over 25,000 volunteers rushed in to help. They pulled out the living, cremated the dead, and adopted villages for long-term rebuilding. Few organizations in the world would claim as part of their work the respectful cremation of more than 3,500 unidentified bodies.

During the 2013 Uttarakhand floods, RSS kitchens provided food to nearly a million people. Roads reopened not through official orders, but through the sweat of nameless young men clearing landslides.

And when Covid-19 brought India to a standstill, the Sangh’s reach extended from isolation centres to plasma donation camps. Its volunteers delivered oxygen cylinders to strangers and performed funerals when families themselves were unable to attend. The numbers are staggering: over a hundred care centres, thousands of food packages, and thousands of funerals performed in anonymity.

This is the paradox of the RSS: An organization accused of being secretive, whose work has often been most visible in times of despair — yet least acknowledged in public discourse.

Service during wars

It is not just disasters. In war, too, swayamsevaks have appeared where few expect them.

In 1947, as Pakistani raiders closed in on Srinagar, volunteers helped build a makeshift airstrip that enabled the Indian Air Force to land reinforcements. Without that, many argue, Kashmir’s fate could have been sealed.

In 1962, they trudged to Himalayan villages carrying supplies for jawans. In 1965, they directed traffic in Delhi to allow convoys to move unimpeded. In 1971, they ran refugee camps for millions fleeing East Pakistan. In 1999, during the Kargil conflict, they supported the families of martyrs, provided logistical assistance, and stood in solidarity in a conflict fought on icy heights.

Never in uniform, never in headlines — but always in proximity to the nation’s wounds.

Sangh’s vast network

Beyond the emergencies and the wars lies the long, less glamorous work of institution-building.

The Sangh’s offshoots — Seva Bharati, Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram, Vidya Bharati, Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh — today constitute a civil society empire. They run schools in remote villages, hostels for tribal children, medical centres in slums, and cultural forums across the diaspora.

What began as a daily drill is now a web of organisations touching nearly every sphere of Indian society — education, labour, culture, tribal development, and women’s empowerment.

The hatred the Sangh endures

Yet, the RSS has been shadowed by suspicion throughout its existence. Banned after Gandhi’s assassination, outlawed during the Emergency, and painted as “communal” by its critics, it remains perhaps the most polarising organisation in modern India.

In contemporary politics, Rahul Gandhi and the Congress Party have made the RSS a central villain in their narrative — branding it unconstitutional, dangerous, even fascist. Each election cycle brings new rhetoric against the Sangh.

The contradiction, however, is glaring. An organization that built airstrips in war, ran refugee camps, fed millions in disasters, and carried the dead in pandemics is simultaneously cast as a national “threat.” For its critics, perhaps its real offence is this: it sees India unapologetically through its own civilizational lens.

The RSS has survived not just physical bans, but a century-long narrative war — a war of perception and politics.

The century ahead

What does the next hundred years hold?

The Sangh is already adapting to new realities: environmental movements, digital shakhas, education reforms, and rural empowerment projects. Its ambition is no longer defensive survival; it is assertive nation-building. The vision is of an Atmanirbhar Bharat, confident, rooted, and positioned as a global guide — a Vishwaguru.

The RSS has never contested elections, but its influence has outlived governments and transcended parties. In many ways, it has become the rhythm behind Indian politics — not visible in manifestos, but beating in the background.

As swayamsevaks gather again this Vijayadashami, the hymn rises: “Namaste Sada Vatsale Matrubhumi.”

It was sung in 1925, it is sung in 2025, and it will be sung a century from now.

The Sangh’s real victory is not just that it has endured; it is that its prayer became its practice — and its practice became a century-long testimony of service.