Former Supreme Court judge Rohinton Fali Nariman has once again stirred debate with his remarks on history and secularism. Speaking at a public lecture in September 2025, Justice Nariman warned against what he called “distortions of history” that reduce Emperor Akbar to nothing more than a tyrant and mass murderer.

Justice Nariman argued that Akbar’s reign represented not just military conquest but also cultural patronage and experiments with religious pluralism, such as the Din-i-Ilahi. According to Nariman, erasing these contributions from public memory endangers India’s composite heritage and risks narrowing the country’s civilizational outlook.

This is not the first time Justice Nariman has weighed in on sensitive questions of history and identity. In January 2022, he criticized political leaders for presenting Aurangzeb as a bigot in contrast to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj as a secular king. He instead suggested that rulers like Babar or Akbar offered better models of fraternity. More recently, he has defended the need to guard against communal distortions, whether in political speeches, historical narratives, or judicial reasoning. His latest intervention — this time on Akbar — has reignited the contentious debate over how India remembers its past, and whether Mughal emperors should be framed as symbols of tolerance or as oppressors.

A selective lens: Can a Justice endorse this?

Former justice Nariman is no stranger to controversial statements. In 2022, he dismissed the Aurangzeb–Shivaji contrast as a political gimmick, going so far as to suggest that Babar or Akbar were better symbols of fraternity than the Maratha warrior who fought to protect dharma. In 2024, he branded the Supreme Court’s Ram Janmabhoomi verdict a “travesty of justice,” lamenting that no mosque was rebuilt on the disputed land. This year, he took aim at judges who invoked “divine guidance” in their decisions, calling it a betrayal of the constitutional oath. And now, in September 2025, he has stepped forward to defend Akbar, warning against the “distortion” of reducing him to a tyrant.

But here lies the irony. Nariman’s interventions, always delivered in the name of balance and fraternity, seem to lean only one way. He speaks passionately when a Mughal emperor is portrayed correctly, yet rarely with the same force when their atrocities against Hindus are glossed over. He condemns distortion — but what about the larger distortion that has dominated our textbooks and public memory for decades, where blood-soaked emperors are recast as secular visionaries?

This distortion did not appear overnight. As records show, it began in the 1950s, when little-known writer Gyanchand penned a series of poorly written articles, later promoted by Syed Moinul Haq, an admirer of Aurangzeb. Those fragments were then quoted in Parliament in 1977 by Bishambar Nath Pandey, and eventually canonized in books like Islam and Indian Culture and even the Brill Encyclopaedia of Islam. By the time NCERT textbooks took shape, the damage was complete: temple destructions were “political acts,” massacres were “military necessities,” and trivial land-grant affirmations were paraded as proof of “secular generosity.”

And so, Akbar and Aurangzeb emerged in classrooms as symbols of tolerance, while rulers like Shivaji were stripped of their Hindu identity and portrayed as merely “secular” rebels. This is the whitewashing project — a selective lens that downplays genocide and elevates petty administrative acts into “proof” of liberal rule.

Nariman’s concern about distortion is therefore not wrong — but it is incomplete. For the greater distortion has always been the sanitization of tyranny, the rebranding of bloodshed into “heritage,” and the silencing of Hindu suffering in the name of harmony.

Once a tyrant, always a tyrant

For decades, schoolbooks and films have told us that Akbar was “the Great” — a tolerant emperor, a champion of pluralism, a lover of Hindu princesses, and even the founder of a new faith for harmony. The reality is far darker.

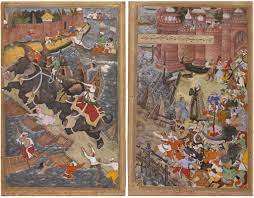

In 1568 at Chittor, after his forces stormed the fort, Akbar ordered the massacre of nearly 30,000 Hindus: men, women, and children. Chroniclers record the bloodbath with chilling details. That was not administration; that was genocide. What do you call a ruler who orders the murder of thirty thousand innocents in a single stroke?

His dealings with Rajput kingdoms are no less damning. Akbar’s “marriages” to Rajput princesses were not romances; they were instruments of submission. Defeated kings handed over their daughters as political hostages, and the harem became a symbol of conquest. The story of “Jodha Bai” — the Hindu wife who supposedly transformed Akbar into a liberal monarch — is itself a colonial invention. As recently acknowledged by the Governor of Rajasthan, there was no queen named Jodha Bai. The British manufactured her to sell the myth of a Hindu princess humanizing a Mughal invader. Bollywood only dressed it up with costumes and songs.

And yet, Akbar’s atrocities, from temple desecrations to forced conversions, are routinely buried under tales of Din-i-Ilahi, Birbal’s wit, or Tansen’s music. A massacre is forgotten; a court musician is remembered. Mass abductions of Rajput daughters are erased; a fake love story is glorified.

The contrast with Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj could not be starker. Shivaji never harmed women, never desecrated temples, and protected his people’s dignity even in war. Yet he is stripped of his Hindu identity in textbooks, reduced to a “secular rebel,” while Akbar is exalted as “Great.”

Once a tyrant, always a tyrant. No amount of fabricated romance, colonial storytelling, or Marxist whitewashing can turn Akbar into a saint. He was a tyrant whose legacy was written in Hindu blood, and the sooner we accept that truth, the freer our history will be.

The wider Mughal record

The dynasty began with Babur (1526–1530), who in his Baburnama openly boasted of razing temples and slaughtering thousands of “infidels.” His conquest of Ayodhya left behind the Babri Masjid, built upon the ruins of the Ram Janmabhoomi temple, one of Hinduism’s holiest sites.

Humayun (1530–1540, restored 1555–1556) carried on this legacy with campaigns in Gujarat and Bengal that destroyed temples and inflicted heavy civilian casualties.

Jahangir (1605–1627), remembered in romance rather than reality, ordered the brutal torture and murder of Guru Arjan Dev in 1606 for refusing to convert to Islam, and ordered further temple demolitions, underscoring the empire’s intolerance.

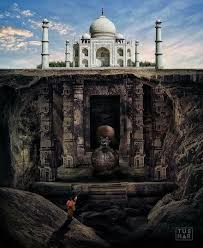

Shah Jahan (1628–1658), celebrated for the Taj Mahal, simultaneously unleashed repression. Contemporary accounts speak of over seventy temples destroyed in Varanasi around an overwhelming number of Hindu festivals, and brutal campaigns that displaced or killed thousands. His marble monuments were built on the backs of subjects bled by war and taxation.

Then came Aurangzeb (1658–1707), the most unapologetic tyrant. In 1669, he ordered the demolition of the Kashi Vishwanath and Mathura temples. In 1679, he reinstated the Jizya tax, a crippling burden on Hindus. On his orders, Sikh Guru Tegh Bahadur was beheaded in 1675. His long reign was marked by endless wars against Marathas, Rajputs, and Sikhs, causing countless deaths, rebellions, and a bankrupt treasury. His own chroniclers boast of bans on music and restrictions on Hindu worship — policies of cultural suffocation.

Supporters may point to Mughal “contributions” in art and architecture, but the historical record also documents massacres, temple desecrations, forced conversions, and systematic humiliation of Hindus and Sikhs. The grandeur of Mughal marble masked a reality of rebellion, repression, and ruin. The empire’s vast map concealed a hollow core — a state that sowed enmity and left behind fractured communities, not fraternity.

The whitewashing project

If the Mughal record is soaked in blood, how did it come to be remembered as a golden age of tolerance and composite culture? The answer lies not in history, but in historiography — the systematic whitewashing of atrocities.

The project of whitewashing Mughal atrocities is alleged to have begun soon after Independence. In the late 1950s, a little-known writer named Gyanchand is said to have published a series of articles in the Pakistan Historical Society Journal. Though poorly written and reported to be riddled with errors, these articles were promoted by Syed Moinul Haq, a historian known for his sympathetic portrayal of Aurangzeb. The message put forth was that Aurangzeb was misunderstood, not intolerant or anti-Hindu. Small administrative acts—such as returning plots of land to Brahmins, reaffirming temple grants, or giving modest stipends to priests—were inflated into supposed ‘proof’ of his generosity. Meanwhile, significant incidents like the destruction of Kashi Vishwanath, Mathura, or the imposition of the Jizya tax often went unmentioned.

From there, the myth snowballed. In 1977, Congress MP Bishambar Nath Pandey quoted Gyanchand’s work in Parliament, later reprinting it in his book Islam and Indian Culture. By the 1980s, these distortions had seeped into NCERT textbooks, presenting Aurangzeb as a “strict administrator” and Akbar as the secular saint of Indian history. Entire generations of students were taught that Hindu–Muslim hostility was a colonial invention, and that Mughal emperors were benevolent rulers maligned by “communalists.”

Western academics added their weight. Audrey Truschke, for instance, claimed Aurangzeb “protected more temples than he destroyed” — as though not demolishing a structure counts as saving it. By such logic, a tyrant who spares one life while taking ten becomes a humanitarian. Similarly, Romila Thapar and Irfan Habib recast temple demolitions as “political acts,” erasing their cultural and religious impact. This academic sleight of hand allowed atrocities to be reframed as routine governance.

Then came the Bollywood gloss. Films like Jodhaa Akbar romanticized forced political marriages as love stories. The very existence of “Jodha Bai,” long debunked by historians and recently by the Governor of Rajasthan, was a colonial fabrication — yet she lives on as Akbar’s great love, softening his image for mass consumption. In popular imagination, Akbar became the wise king of fables, while Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the Hindu protector who never harmed a woman or a mosque, was reduced to a footnote. And nowhere the torturous murder of his son, Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj, found any mention. When someone tried to correct the history, he was labelled as a distortionist.

This is the essence of the whitewashing project: elevate trivial administrative gestures into evidence of “secularism,” erase massacres and demolitions, invent romances to humanize tyrants, and suppress Hindu suffering in the name of harmony. The result is a historical narrative where invaders are glorified as nation-builders, and resistance is minimized as parochial rebellion.

The fury against truth

Former Justice Nariman is right about one thing — distortion of history is dangerous. But the deeper question is this: whose distortion are we really living with? For decades, the Indian mind has been conditioned to see Akbar as “Great,” Aurangzeb as “misunderstood,” and the Mughals as civilizers. Massacres are forgotten, demolitions explained away, rapes and forced conversions erased. A dynasty that bled India for centuries has been rebranded as the fountainhead of India’s “composite culture.”

And yet, whenever someone points to Chittor’s 30,000 dead in 1568, to the destruction of Kashi Vishwanath in 1669, or to the execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur in 1675, the reaction is fury. Tell the truth, and you are called “communal.” Expose the brutality, and you are accused of spreading hate. Write about a former justice’s selective lens on history, and you fear contempt of court. Even a retired Supreme Court judge, speaking in the name of fraternity, defends Akbar’s “heritage” while dismissing the blood that bought it.

Why is it so intolerable to acknowledge Hindu suffering? Why are temple demolitions airbrushed, but a fabricated “Jodha love story” is repeated as fact? Who benefits from a history where invaders become icons and victims are told to forget?

The real distortion is not in remembering Akbar as a tyrant — it is in pretending he was not one. And the anger that greets this truth only proves how fragile the myth has become.