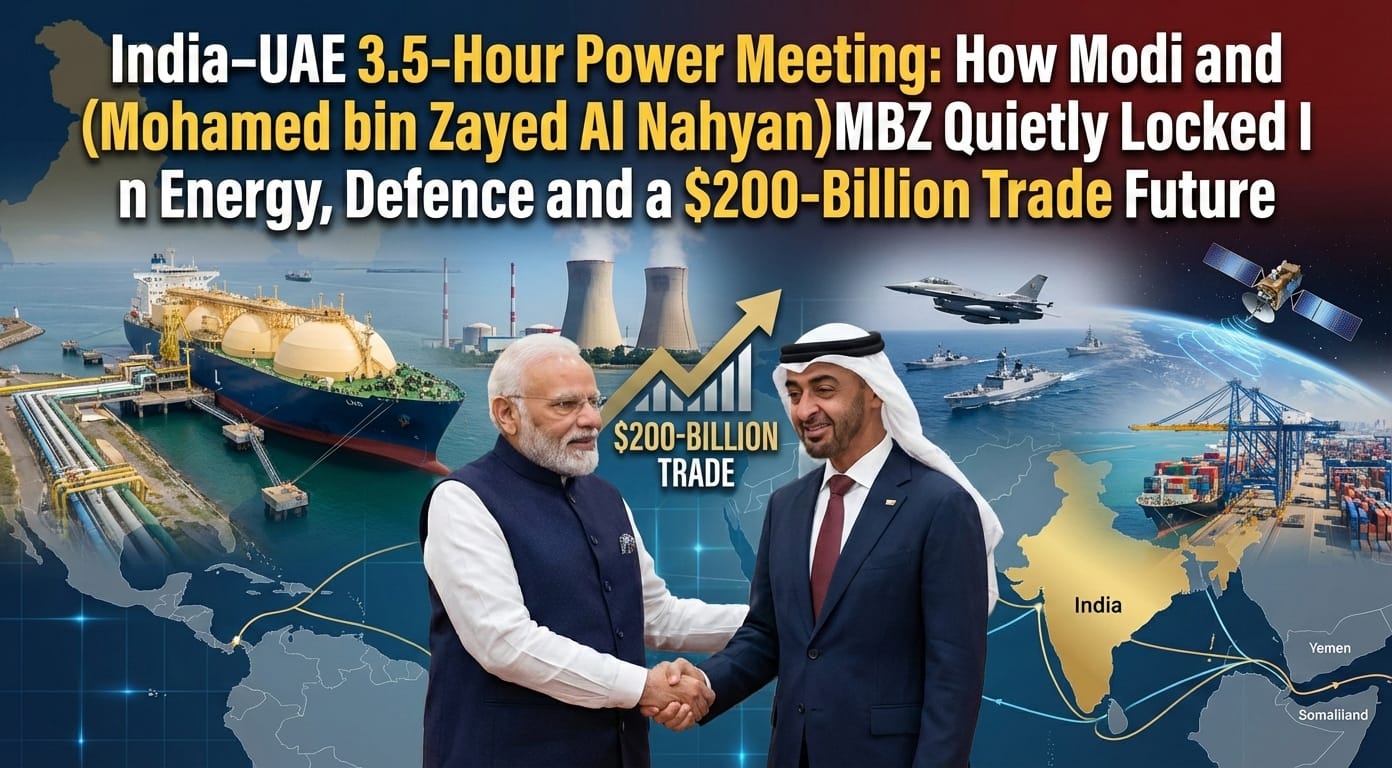

In Delhi, the choreography was unusually personal. Prime Minister Narendra Modi received Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (MBZ) at the airport, only the second time he has done so for the UAE ruler after December 2024, a protocol reserved for a handful of leaders in over eleven years.

The Emirati side flew in a heavy‑hitting team—Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed (foreign minister), the Crown Prince of Dubai Sheikh Hamdan bin Mohammed, senior defence and AI ministers, the head of the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and national security officials—signalling that the agenda was not ceremonial but strategic.

Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri later called it an “extremely substantive” visit and, crucially, used the same press briefing to draw a red line: India’s deeper defence and security cooperation with the UAE “does not necessarily lead to the conclusion that we will get involved” in the region’s conflicts.

That sentence is the key to reading everything else that follows.On paper, the meeting produced five formal agreements and seven “outcomes”, but together they amount to a kind of ten‑year roadmap. First is energy: ADNOC Gas and HPCL signed a 10‑year LNG Supply Agreement for 0.5 million tonnes per year starting 2028, a deal estimated at around $3 billion that quietly makes the UAE India’s second‑largest LNG supplier and locks in volumes in an era of volatile spot prices.

Second is defence: a Letter of Intent was inked to negotiate a Strategic Defence Partnership framework, covering defence industry collaboration, advanced technologies, training and exercises, taking what was already robust cooperation—frequent visits by service chiefs and joint drills—into a more institutional, long‑range space.

Third is space and tech: an LoI between IN‑SPACe and the UAE Space Agency set up a joint initiative on space infrastructure and commercialisation, with plans for launch complexes, satellite manufacturing, joint missions, a space academy and training centres, while other understandings cover a super‑computing cluster in India, AI collaboration and food safety.

The economic spine is just as important. The joint statement notes that bilateral trade has already hit about $100 billion in FY 2024‑25 under the 2022 CEPA, and both sides now want to double this to $200 billion by 2032, a target that is deliberately stretching. This is tied to very specific projects: a Letter of Intent for UAE participation in the Dholera Special Investment Region in Gujarat, with an international airport, pilot training school, MRO facility, greenfield port, smart township, rail links and energy infrastructure, effectively inviting Emirati capital to create a new logistics‑aviation hub on India’s west coast.

They also agreed to push “Bharat Mart” as a physical‑digital hub for Indian exporters in the UAE, build a “Virtual Trade Corridor” to cut paperwork, and develop a “Bharat‑Africa Setu” to route MSME goods from India to the Middle East, Africa and Eurasia through Emirati ports.The financial plumbing will be upgraded through interlinking national payments platforms for cheaper, faster cross‑border transactions, and both sides will examine the idea of a digital or data embassy hosted in the UAE under Indian jurisdiction—an unusually high‑trust move in the data sovereignty space.

A less visible but strategically sensitive track is nuclear. The joint statement explicitly “welcomed” India’s new SHANTI law (Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India), reading it as an opportunity for expanded civil nuclear cooperation. The two sides agreed to explore partnerships on large nuclear reactors and Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), and on advanced reactor systems, plant operations, maintenance and safety—areas where the UAE brings experience from its Barakah plant and India brings decades of nuclear engineering and regulatory practice.

In parallel, the leaders hardened their language on terrorism: they “unequivocally” condemned terrorism “including cross‑border terrorism”, insisted that no state should offer safe havens, and pledged to keep working within the FATF framework to clamp down on terror finance and money laundering.

For Delhi, that phrasing—especially “cross‑border”—is a subtle but important diplomatic win in the Gulf.All this is happening while the ground shifts violently just across the water. In Yemen, the Saudi–UAE partnership that once drove the anti‑Houthi war is fracturing into open rivalry.

Detailed work by the Arab Gulf States Institute, Middle East Institute and others shows how Abu Dhabi has built up the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and allied forces, focusing on southern Yemen and key coastal cities like Aden and Mukalla, while Riyadh backs the internationally recognised Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) and demands a unified Yemeni state.

Late 2025 and early 2026 saw STC‑aligned forces push into Hadramaut and Mahrah—oil‑rich and border provinces that Riyadh treats as “red lines”—prompting Saudi air strikes, cancellation of defence deals with the UAE and accusations that Abu Dhabi wants to carve out a de facto “South Arabia” along critical sea lanes. Reports cited by Responsible Statecraft and others stress that UAE‑linked forces now hold a patchwork of strategic sites along the Gulf of Aden and parts of the Red Sea coast, giving Abu Dhabi leverage over the Bab el‑Mandeb chokepoint even as Houthis threaten shipping from the north.

Somaliland and the Horn of Africa are the other half of this maritime story. The Vivekananda International Foundation notes that Ethiopia’s controversial MoU with Somaliland offered Addis Ababa a 20‑kilometre strip of Red Sea coastline near Berbera for 50 years, in return for recognition of Somaliland and a stake in Ethiopian Airlines, giving landlocked Ethiopia long‑sought sea access.

Long before that, the UAE’s DP World had taken a 51 percent stake in Berbera Port and has now launched a regular shipping corridor between Jebel Ali in Dubai and Berbera, turning the port into a growing logistics hub facing Yemen. Analytical pieces from Al‑Estiklal and regional think tanks argue that, taken together, UAE bases and port deals in Berbera, Eritrea and southern Yemen form an “arc” of influence across the Red Sea–Gulf of Aden, allowing Abu Dhabi to shape trade flows, naval deployments and even gas export routes, at times in competition with Saudi ambitions around Vision 2030 and Red Sea security.

Seen against this map, the Delhi meeting becomes easier to decode. By locking in a 10‑year LNG line from the UAE, India is insuring itself against disruptions in other gas routes, including those that might be affected by escalation around Bab el‑Mandeb or in the Eastern Mediterranean.

By inviting Emirati capital into Dholera’s airport, port and logistics infrastructure, and welcoming DP World and First Abu Dhabi Bank into GIFT City, New Delhi is effectively tying its own west‑coast hubs into the same network of Gulf‑Horn ports that DP World and Emirati planners are building from Berbera to Jebel Ali—except here, India is producer, not just customer.

Civil nuclear cooperation and a data embassy are less about Yemen directly and more about signalling that, unlike many Western partners, the UAE is willing to be embedded in India’s long‑term energy and digital sovereignty agenda, while India is comfortable treating Abu Dhabi as a strategic, not just transactional, partner even as it talks to Saudi Arabia, Iran and the US on Gaza and the Red Sea.

Vikram Misri’s insistence that India’s defence ties with a Gulf state “do not necessarily” mean it will be drawn into regional conflicts is therefore not hedging; it is policy. India wants Emirati LNG, ports, capital and technology; it wants to co‑shape rules on payments, data and counter‑terror finance; it even wants to plug into UAE’s emerging maritime web in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa.

But it does not want to choose between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi in Yemen, nor be seen as taking sides in the Ethiopia–Somaliland gamble or any future flare‑up between UAE‑backed forces and Saudi‑backed coalitions. That is why the joint statement leans so heavily on “strategic autonomy” and “sovereignty”, and why India is simultaneously talking to the Emiratis about Gaza and Yemen while keeping its own naval deployments in the Arabian Sea focused on anti‑piracy, convoy escort and humanitarian tasks rather than coalition warfare.

In that sense, the Delhi meeting is both narrow and very broad. Narrow, because its hard outcomes—LNG tonnage, LoIs, Dholera, data embassies—are all bilateral and technocratic. Broad, because each of those lines is actually a bet on how the region around Yemen and Somaliland will evolve: more fragmented, more militarised and more central to global trade.

Modi and MBZ have, in effect, agreed that India and the UAE will deepen their interdependence across energy, defence, nuclear, trade and data at the very moment when old coalitions in West Asia are breaking apart.

The real story is not that India is choosing sides, but that it is choosing a partner—and trying, through deals like these, to make sure that its sea lanes and growth story survive whatever storms Yemen, Berbera or Bab el‑Mandeb throw up in the decade ahead.