When India and the European Union concluded their long-pending Free Trade Agreement (FTA), it was swiftly labelled the “Mother of All Trade Deals.” The phrase is not hyperbole. In scale, scope, and—most importantly—timing, the India–EU FTA represents one of the most consequential economic alignments India has undertaken in decades. It goes beyond tariff reduction and speaks directly to how India intends to navigate a fragmenting global trade order increasingly shaped by geopolitics rather than efficiency.

Together, India and the EU represent nearly two billion consumers and close to a quarter of global GDP. Bilateral trade already exceeds USD 215 billion across goods and services, and the agreement liberalises almost 99.5% of Indian exports to the EU by value and around 96% of EU exports to India, largely through phased tariff reductions. Yet the real importance of the pact lies not in tariff arithmetic but in its strategic intent: repositioning India as a resilient, trusted, and rules-compliant economic partner at a time when global trade predictability is under strain.

India–EU FTA at a Glance

| Share of global GDP: ~25% |

| Bilateral goods trade: USD 135+ billion |

| Bilateral services trade: USD 80+ billion |

| Indian exports liberalised: 99.5% (by value) |

| EU exports liberalised: ~96% |

Timing matters in an uncertain trade environment

Practically speaking, the timing of this agreement carries considerable importance. Global trade today is no longer driven solely by cost efficiency or comparative advantage. It is increasingly shaped by supply-chain resilience, diversification, and strategic autonomy. Rising protectionism, unilateral tariffs, export controls, and industrial subsidies—particularly among major economies—have eroded predictability in global commerce.

India’s exposure to these risks is tangible. Nearly 18% of its merchandise exports are destined for the United States, where tariff rhetoric and trade policy volatility have intensified. Against this backdrop, the EU FTA functions as strategic insurance. Preferential access to a large, affluent, and relatively predictable market such as the EU reduces India’s dependence on any single destination and cushions it against sudden trade disruptions elsewhere.

Beyond Tariffs: Rules of Origin and Integration

A critical pillar of the agreement lies in its rules of origin, closely aligned with those used in the EU’s newer generation of FTAs. These rules perform a dual function. On one hand, they preserve the integrity of tariff concessions by preventing trans-shipment and superficial value addition. On the other, they actively encourage deeper manufacturing integration and genuine value creation within partner economies.

In doing so, the FTA nudges Indian firms away from being low-cost, volume-driven exporters toward becoming trusted suppliers embedded within European value chains. This shift has implications far beyond trade balances, influencing technology transfer, productivity growth, and export resilience.

Export expansion and sectoral gains

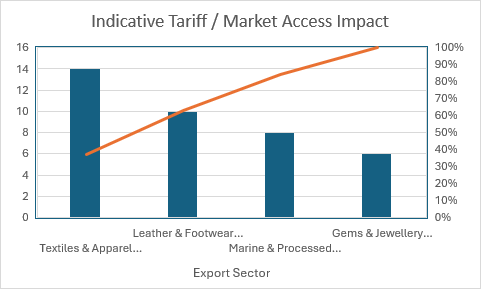

The most immediate macroeconomic impact of the FTA will be felt through exports. Indian goods will benefit from duty elimination on over 90% of tariff lines, significantly improving competitiveness in the EU market. Labour-intensive sectors such as textiles and apparel, leather and footwear, gems and jewellery, marine products, and processed foods stand to gain substantially, particularly where earlier tariff barriers ranged between 8% and 16%.

For pharmaceuticals, chemicals, engineering goods, and electronics, gains will be driven less by tariff elimination and more by regulatory alignment, compliance predictability, and clearer rules of origin. Over time, this is likely to reshape India’s export basket away from low-margin volume exports toward higher-value, standards-compliant products suited to advanced markets.

Reciprocity as a productivity lever

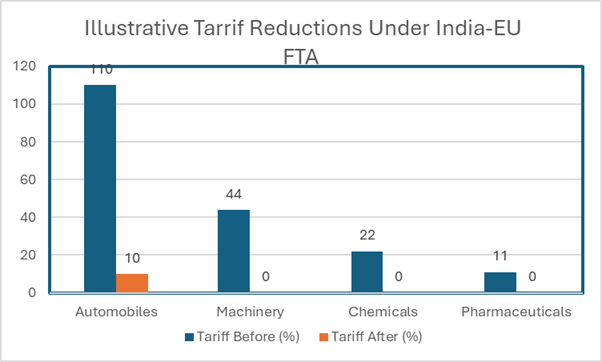

The agreement is deliberately reciprocal. India has agreed to gradually reduce tariffs on European automobiles from 110% to 10% and abolish duties on auto components within five to ten years. Tariffs on machinery, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals—previously as high as 44%, 22%, and 11%—will also be sharply reduced or eliminated.

While these changes have triggered short-term market reactions, the competitive pressure is structural rather than accidental. Cheaper access to advanced European machinery lowers production costs, accelerates technology absorption, and improves manufacturing productivity. Historically, successful industrialisers sequenced competition rather than avoiding it; the phased structure of this FTA reflects that logic.

Investment, Services, and Geopolitics

The FTA also enhances India’s attractiveness for European investment in automobiles, electronics, renewable energy, green hydrogen, pharmaceuticals, and advanced manufacturing. Rather than remaining an exporter of finished goods alone, India is positioned to become an integral node in European production networks. Agriculture and services benefit as well, through improved market access, mobility provisions for skilled professionals, and alignment with inclusive growth objectives.

Ultimately, the India–EU FTA must be read through a geopolitical lens. In a world defined by trade wars, supply-chain uncertainty, and weakening multilateralism, the agreement anchors India more firmly in a predictable, rules-based trading system. The “Mother of All Trade Deals” will be judged not by tariff lines liberalised, but by how effectively India converts market access into long-term competitiveness and strategic economic influence.

India 2026–2030: From market access to market power

Between 2026 and 2030, the India–EU FTA could shape India’s external sector in three critical ways. First, it can rebalance exports toward higher-value goods and services, improving terms of trade. Second, it can embed India more deeply in global value chains, reducing vulnerability to tariff shocks. Third, it can enhance India’s credibility as a long-term economic partner capable of meeting global standards.

The agreement, however, is not self-executing. Indian firms—especially MSMEs—will need support to manage compliance costs and scale up capabilities. The real test will be whether India converts preferential access into competitive advantage.

Thus, while concluding It can be said that India- EU agreement is explicitly framed around the FTA, recent Union Budgets align closely with its objectives. Higher capital expenditure, logistics modernisation, production-linked incentives, and a focus on manufacturing competitiveness complement the opportunities created by the agreement. The “Mother of All Trade Deals” is not about tariff lines; it is about leverage.

The India–EU Free Trade Agreement is not merely about tariff reduction—it is about repositioning India in the global economic order. By combining export expansion, manufacturing competitiveness, agricultural growth, services mobility, and sustainability, the agreement lays the foundation for a more resilient, diversified, and future-ready economy.

Ultimately, the success of this “Mother of All Trade Deals” will be measured not by the number of tariff lines liberalised, but by how effectively India converts preferential access into long-term competitiveness, supply-chain integration, and global economic influence.

Author Dr. Bhavana Rai is serving as a Joint Director at the FHRAI Centre of Excellence for Research in Tourism and Hospitality (CERTH),and is a regular contributor on public and academic platforms as a subject expert.