For more than a decade, India’s electricity distribution companies – the discoms that sit at the politically sensitive frontline between state governments and consumers – were best known as the weakest link in the power chain, bleeding tens of thousands of crores every year and routinely delaying payments to generators.

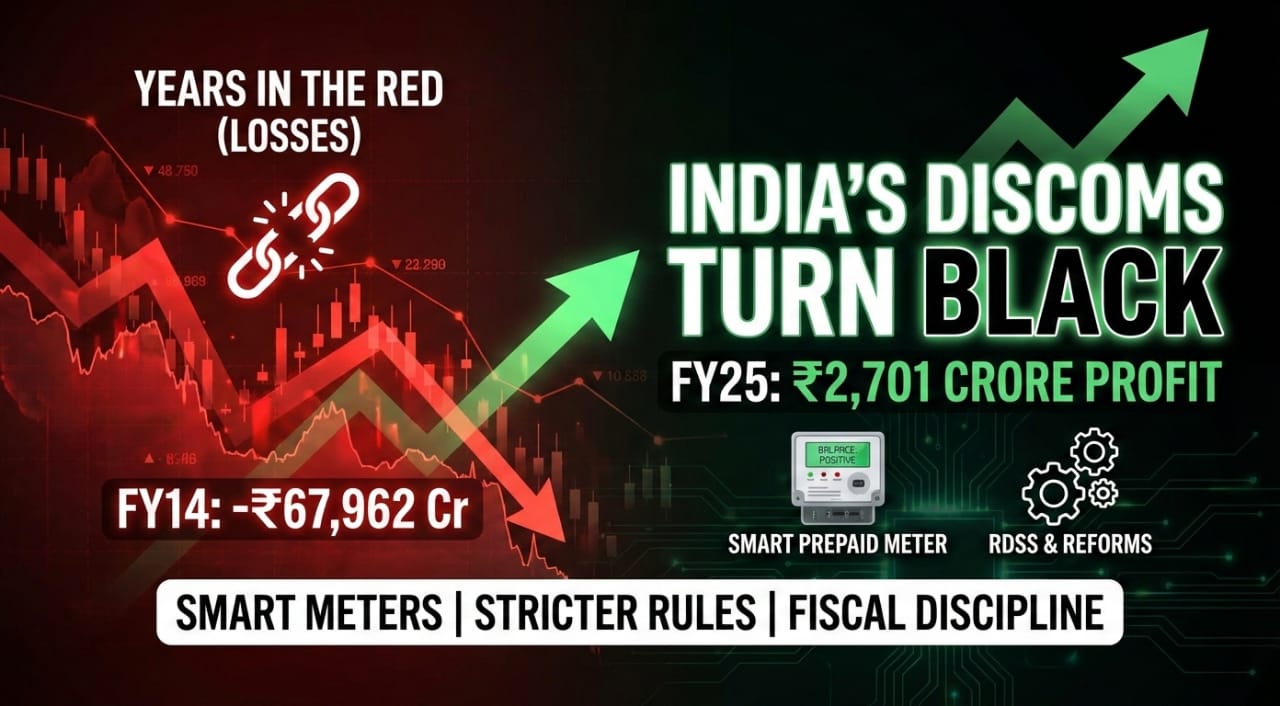

That narrative has been dramatically upended with the Union Power Ministry announcing that distribution utilities have collectively posted a Profit After Tax of ₹2,701 crore in FY 2024-25, the first return to profitability since state electricity boards were unbundled.

The turnaround is stark when set against the past: The same entities reported a loss of ₹25,553 crore in FY 2023-24, and an even deeper loss of ₹67,962 crore in FY 2013-14, when chronic under‑recovery, high losses and delayed subsidies had pushed the system towards what many analysts then described as “quasi-insolvency.”

Power Minister Manohar Lal Khattar has framed the shift as “a new chapter for the distribution sector,” arguing that sustained reforms have finally begun to restore financial and operational stability and position the power system to support India’s next phase of economic growth.

At the heart of this story is the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS), launched to attack both the physical and financial leakages that had long undermined discom balance sheets. Under RDSS, the Centre has funded and nudged states to modernise wires, transformers and substations while aggressively rolling out smart prepaid meters for consumers, feeders and distribution transformers, thereby tightening the data loop from consumption to billing.

Officials say this combination of hardware upgrades and digital metering has directly improved billing efficiency, reduced theft and slashed so‑called “aggregate technical and commercial” losses that used to quietly eat away at revenues.

The numbers suggest that operational gains are not just incremental but structural. Aggregate technical and commercial (AT&C) losses – a composite measure capturing both line losses and commercial leakages like theft, faulty meters and poor collection – have fallen from 22.62% in FY 2013-14 to 15.04% in FY 2024-25.

In parallel, the gap between the average cost of supply and average revenue realised (the ACS–ARR gap) has narrowed from ₹0.78 per unit in FY 2013-14 to just ₹0.06 per unit in FY 2024-25, indicating that discoms are now recovering virtually all of their supply costs, a sharp departure from the era when every unit sold deepened their losses.

If RDSS has been the engine, a new regime of fiscal discipline has been the brake on old habits. The Centre has tightened prudential norms, linking access to additional borrowing and central support to performance on key operational benchmarks such as loss reduction, timely billing and collection, and metering progress.

This has effectively forced states and their discoms to treat basic utility housekeeping – from closing the gap between billed and collected energy to clearing past dues – as preconditions for fresh money, rather than optional reform promises.

A parallel set of changes has played out on the regulatory side through amendments to electricity rules that target the chronic misalignment between tariffs, subsidies and costs. New provisions have pushed state regulators and governments towards more regular tariff revisions, transparent subsidy accounting and tighter cost recovery, reducing the fiscal slippage that once accumulated as hidden losses on discom books.

The Electricity Distribution (Accounts and Additional Disclosure) Rules, 2025, have further standardized accounting across states, making it harder to mask arrears or postpone the recognition of losses and enabling a clearer, comparable view of utility performance nationwide.

The most visible beneficiary of this new discipline has been the upstream segment: power generators and transmission companies that long complained of delayed payments and ballooning receivables from state distributors.

Under the Electricity (Late Payment Surcharge and Related Matters) Rules, utilities face financial consequences and potential curbs on grid access if they default, which has sharply changed incentives around timely payment.

As a result, outstanding dues to generating companies have collapsed by 96%, from ₹1,39,947 crore in 2022 to just ₹4,927 crore by January 2026, while the average payment cycle has shortened from 178 days in FY 2020-21 to 113 days in FY 2024-25, easing liquidity pressures across the power supply chain.

Behind the aggregate numbers lies a politically delicate process of Centre–state bargaining. The Power Ministry has used a mix of carrot and stick: incentives for states that undertake reforms under the Additional Borrowing Scheme, and persistent engagement through a series of regional conferences of state and Union Territory energy ministers held in 2025 in Gangtok, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chandigarh and Patna.

These forums, led by Power Minister Manohar Lal Khattar, have been used to push states on smart metering timelines, loss reduction trajectories and tariff rationalisation, while also addressing local concerns over consumer backlash and the political economy of higher power bills.

Yet even as the FY25 profit numbers spark understandable celebration, experts caution that the structural vulnerabilities of India’s distribution segment have not vanished overnight. AT&C losses of around 15% remain far above global best practice, and there are wide inter‑state disparities, with some utilities still struggling with theft, poor billing and mounting subsidy dependence.

Moreover, as India ramps up renewable capacity and electrifies more of its economy – from mobility to industry – the pressure on discoms to invest in flexible networks and smart systems will only increase, making sustained tariff discipline and subsidy targeting essential to avoid a relapse into the red.

For now, the ₹2,701‑crore profit is less a destination than a proof of concept: that a combination of infrastructure modernisation, digital visibility, regulatory tightening and fiscal conditionality can, together, shift a politically constrained public utility model towards viability.

As the Centre projects the power sector as a pillar of India’s ambition to become a developed economy, the real test will be whether this fragile turnaround can be deepened and replicated across all states, turning an exceptional year into a new normal rather than a fleeting statistical high.