Prime Minister Modi’s celebration of the eternity of Somnath Mandir is a pronounced denial of a coercive past thrust upon Bharat and Hindus. Somnath Swabhiman Parv is a symbol of Hindu courage staring down civilisational trauma through the warming flame of mantras, auspices and nation building.

Modi’s India is creatively-avenging the conquest of Bharat’s sacred geography through the fervour of freedom. It has a basis in the life and sacrifices of Hindus who understood the intentions of desecration of mandirs and spaces sacred to the Hindus.

The transmutation of civilisational friction between those who operate cultural destruction with the cruel-footing of religious supremacy and those who protect, and avenge, by rebuilding in trauma, continues. But the civilisational arc of the Hindu cultural upsurge has been bent upwards, towards the dharmadhwaja, towards the shikhara of Somnath and Ayodhya, once again, in Independent India.

For this, Modi’s own striking intervention marking the 1,000 years of Hindu resilience, would be incomplete without underlining KM Munshi’s contribution to the rebuilding of Somnath Mandir.

The weight of a thousand years of the iconoclast’s marauding, contemptuous and murderous gaze and axe has perished in every breath chanting the Omkar Mantra during the rituals marking the Somnath Swabhiman Parv at the Somnath Mandir. Marking the thousandth anniversary of the first recorded attack on Somnath by Mahmud of Ghazni during the unfurling of the dharmadhwaj at Ram Mandir, during the year of Operation Sindoor, Modi’s Bharat has etched a message of continuing cultural restoration and spiritual preservation — on the scroll of the 21st century. The Somnath Swabhiman Parv should become an occasion for rediscovering our collective learnings in cultural unity.

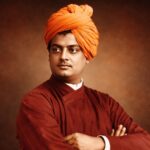

KM Munshi – The restorer bridging Devi Ahilyabai Holkar and PM Modi

The message of civilisational resilience, celebrating the sustenance of dignity and honour. It might take Bharat and the devotee centuries to continue sustaining and fuelling civilisational resilience with worship, blood and sword, but the ammunition comes from faith, from the vigrahas, the garbha grihas and the mandapas of our temples. They nourish the indomitable courage of the devotee – the Bharatiya, the foot soldiers of dharma and shapers of statecraft. Independent India’s deep understanding of the pace of destruction and restoration between the Ghazni and Aurangzeb, provide rigour to the understanding of “shatrubodh”, but more importantly, it empowers the process of preservation in rebuilding and restoration of the living abodes of dharma. Today, it fosters the fusion of military strength, dharma, and cultural resurgence in an India that can visualise sovereignty from Prabhas Khanda.

Every moment of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s presence in the Shaurya Yatra, the symbolic procession dedicated to the memory of the unknown devotees of Somnath, is a symbolic tribute to every step taken, every drop of blood shed, for the protection and preservation of the abode of the deity for centuries. “Jai Somanatha”, it is.

As India remembers the protectors, re-builders and restorers of Somnath Mandir, the collective resolve for preservation led by Devi Ahilyabai Holkar and other Hindu devotees, it is important to view KM Munshi and his contribution as that one jewel in a movement that bridges the eras of Devi Ahilyabai Holkar and PM Modi – the two giant restorers in different centuries.

KM Munshi to PM Modi – The journey in understanding cultural freedom

From Munshi to Modi, the journey of a single goal — celebrating the alchemy of Somnath, which itself is defined by the devotee’s unconquered, unsubdued, perseverance — has been marked by a creative urge to align dharmic continuity with cultural restoration. Like Munshi, PM Modi may not have been able to earn the time and creative bandwidth to study the ruination and rebuilding of Somnath for a thousand years, but he is moving in the same direction as Munshi, by choosing to value and honour the dignity of the Hindu bhakta for tragedies that took place 500 years ago — in the case of Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. For a thousand years – in the case of Somnath. Munshi’s creative goal was to provide the Bharatiya a confluence of freedom and potential space and opportunity to realise individual creative potentials.

There isn’t a particular cultural prototype for it that Munshi suggested, but there’s definitely a process, a paradigm in creation, that transpires in the “goal” he envisioned. Munshi’s concept of the goal was seeking a congruence in the social and the individual, the gradual metamorphosis of human capabilities – sustained by devotion and the human urge to be the instrument of the divine. “God” remains central to it. The temple, the abode of Somnath, remains central to it. PM Modi has exhibited, expressed and executed his own understanding of cultural freedom in his restoration and rejuvenation of Hindu swabhiman — with temples as its sacred symbol.

When “Jaya Somanatha” defeated political cowardice

“So it is Jaya Somanatha.” According to Munshi, these words spoken by Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel to KM Munshi underlined the new development in the incoming telephonic message from Buch, the Saurashtra commissioner in the government of India who urged for assistance to hand over the administration directly to the Indian Union. Buch informed Patel that the Nawab of Junagadh invited the Indian Army to Junagadh. November 12, 1947, happened to be Deepawali. Patel visited Junagadh accompanied by Jam Saheb. At the premises of Somnath Mandir, Patel looked at the sea and walked towards it. He held some sea water in his palms, and uttered that his ambition was fulfilled, before silently walking back to the temple.

At the onset of the new year, from the temple built by Devi Ahilyabai Holkar, Patel announced that the Somnath Temple should be rebuilt. Jam Saheb announced a donation of Rupees One Lakh for the reconstruction. Samaldas Gandhi, the activist and force behind the newspaper Vande Mataram, representing the administrator of Junagadh, donated Rs 51,000.

According to Munshi’s account, addressing people at the huge public gathering, Patel said: “You, people of Saurashtra, should do your best. This is a holy task in which all should participate.” Munshi witnessed, “awestruck”, examining parts of the old structure and other remains of importance, tangible evidence of Hindu art, architecture and heritage of beauty, that emerged in the excavations conducted by BK Thapar under the Department of Archaeology.

Munshi was on a civilisational mission to see Somnath rebuilt. Munshi’s mission became indefatigable and immune to political arrogance, pusillanimity, and cowardice of a leader who should have ideally understood the importance and the urgency to build Somnath during the same year as India’s Partition. Imagine the strength of determination that managed to bring together the minds and material that were required for the rebuilding of Somnath, against that one voice that seemed compulsively resolute to throw a clog in the “swabhiman” wheel of Hindu devotion and civilisation justice.

The iconoclast’s marauding gaze on Somnath

Bharat and Hindus had a reason to place profound trust in Somnath. It was rooted in their response to their own tragedy. When they saw the iconoclast gaining success in different parts of Bharat, the impending notion, that Somnath was displeased with the idols, struck them. The Sultan’s march from Ghazna to decimate the power of Ganda, Kannauj and Bari (1019 according to another account on the conquests of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna) preceded his march to Somnath. With swelling armies after each conquest, the marauder destroyed what came his way. He returned to Ghazna. In 1025, October, he left Ghazna, reached Multan a month later, and prepared to travel across the desert with the help of camels and water loaded on them. Hindus made their first attempt to put up resistance at Mundhera, according to one source. They were defeated.

The date of this iconoclast’s arrival in Somnath is January 6, 1026, according to Munshi. The fortress on the seashore was captured. Brahmins and devotees, together, fought to protect the idol on that day and the next, with a furious attack. The number of Hindus perished in the waves of attacks to defend the deity is mentioned as more than 50,000. Axes and fire were used to destroy the idol and the temple. The abode of Somnath was plundered, razed and burned. Raja Paramadev from Abu, mention Munshi’s account and another account, advanced with his wrath to block the marauders’ path of retreat. For this, he stood as an obstacle at the stretch of land that connects the Aravali Hills and the Rann of Kutch. The Sultan decided to bypass the obstacle by marching through Kutch and used the low tide in the sea to cross over to the other side. In Kutch, the unsuspecting Sultan was misguided by a devotee of Somnath, who was so angered by the devastation of the deity’s abode, that he compelled the army to wander off into a stretch where water was in scarcity. This act of revenge made the Sultan and his army face a dangerous circumstance, from which he eventually managed to wriggle out.

On his way back, in Multan, the Sultan had to deal with the impacts of another adversary – the Jats. According to an account, the conquest of Somnath was considered one of the “greatest” victories in the Islamic world. The Sultan was honoured in a series of titles and gifts. His glorification, perhaps, was destined to be an event of the century. In 1027, the Sultan would punish the Jats for putting his army through trouble in his retreat from Somnath to Ghazna. A blood shed was strategised and posed on the Indus with the help of boats, arrows and other materials of attack to stun the Jats. The Jats suffered defeat.

The element of resurgence is palpable in Munshi’s reception of events of late 17th century India. He uses the term “Hindu India” while referring to the readiness of India to unseat and subvert the rule of Aurangzeb. The rise of the Sikh gurus, the Marathas, and Rajput rulers was assembling towards a build up of powers that would avenge the destruction of Somnath ordered by Aurangzeb in 1706. In the presence of grief was the fruition of hope and homage as the Marathas improved their influence on Gujarat. In 1783, Devi Ahilyabai Holkar secured the Linga in a discreet abode below the upper abode and by the beginning of the 19th century, Saurashtra was secured by the Gaekwad of Baroda.

The spell of determination, Munshi, Modi and Nehru’s legacy – Then and now

There could be some hint of bias in my viewing of the efforts of Munshi to build a harmony between individual efforts, the social, cultural with Somnath at the core of Hindu revival. Yet there is nothing absolutely to justify Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s direct dislike of Munshi’s efforts to restore Somnath. Nehru’s words grumbled: “I don’t like you trying to restore Somnath. It is Hindu revivalism.”

The Hindu healing initiated by Munshi is ongoing. The Ramjanmabhoomi movement has its seed in Somnath and its alchemy of resilience. The building of Ram Mandir in Ayodhya was the establishing of honour and the erasure of shame and darkness. PM Modi participated in both and led from the front. This year, PM Modi was present at the ceremony of the installation and unfurling of the dharma dhwaja at the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. Nehru’s rejection of Hindu healing, which eventually would result in Hindu revivalism revved up by Munshi’s determination and action focussed on Somnath. Munshi remained steadfast to his role. This has a parallel in the denunciation PM Modi faces from members of Nehru’s own family members and the counter movement Modi erects, gently but firmly, each time, by remaining present and consistent for the reconstruction, honour and rejuvenation, of temples and temple life.

When one views Munshi’s exploratory pursuit of Somnath, his commitment to the conversion of his personal passion for Somnath’s restoration into a common and collective national project for Bharat’s dignity, and self esteem, with a lens of complete neutrality, one understand why Nehru found himself decently aloof with Munshi, Patel and President Dr Rajendra Prasad on the other side. Dr Prasad led the installation of the lingam at Somnath on May 11, 1951. Munshi’s mental and emotional clarity – regarding the rebuilding of Somnath Mandir, the symbol of Bharat’s national consciousness as the national pledge — helped him drive the humongous task of the temple’s restoration in the absence of Patel (due to his demise). After India’s Independence and Junagadh state’s accession into the Indian Union, Patel pledged that the original glory of Somnath will be restored and preserved. Munshi managed that conversion – from determination and desire – to action and execution through and with Patel.

In hindsight, Nehru’s reaction was unfortunate, disappointing, but expected. As India’s current prime minister Narendra Modi participates in the celebration of Somnath and the devotee’s resilience to preserve, Nehru will be understood as a contrast. As an Indian and prime minister (the first), he clearly (and perhaps willingly) fumbled in comprehending the deeply spiritual importance of the political, social, cultural and spiritual in Somnath’s restoration.

Political — the accession of the Junagadh state in into the Indian Union; social — the harmony, relief, and the protection of the individual and collective temperament of the devotee of Somnath in Independent India; cultural – the restoration of sensibilities attached to Somnath and its percolation in pan-India consciousness; spiritual — the transmutation of the devotional aspect surrounding Hindu revival and its securing with the physical restoration of Somnath.

Nehru and Nehru’s lineage have been consistent in being displeased with political participation in the rebuilding of the Somnath Mandir to insulate their “secular” credentials from the larger and overall civilisational triumph resting on the ancient glory of Somnath Mandir as well as the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. Even though the events are separated by seven long decades, one constant – through the transformational series of changes – has been the calculated avoidance of Nehru’s legacy and the Gandhi family from “rebuilding” reflected in the restoration of Somnath and the building and celebration of Ram Mandir. They have stood opposed to the political cycle of rejuvenation.

In my opinion, Gandhi’s suggestion — that the contribution of Somnath’s restoration and rebuilding should come from the public – eventually worked like a blessing in disguise. Here is why. Nehru was not displeased with Munshi alone for efforts to restore Somnath. The feeling was common when he viewed the participation of Dr Rajendra Prasad, who made it clear in his written response to Nehru that he was approached by Jam Sahib of Nawanagar to “preside over” the ceremony. The snub was tacit. Dr Rajendra Prasad wrote: I personally do not see any objection to associating myself with the function, particularly because I have never ceased visiting temples, and…denominational religious or semi religious institutions.” Nehru received the defiance he deserved in this matter.

Dr Rajendra Prasad not only travelled to Gujarat for the ceremony, but also presided over the Pran Pratishtha, closing the gargantuan outlet of Hindu humiliation and cultural indignity for centuries. Munshi, Prasad and Patel, together, ensured that Bharat did not enter and chronicle a new era with the open wounds of dishonour to Hindu heritage. They ensured that India did not remain enslaved by centuries of coercion displayed in the scattered and neglected ruins of Somnath. They realised freedom through rebuilding it.

This would have been impossible without Munshi becoming the changemaker, the backbone and the visionary bearing a students’ curiosity and a Hindu lawmaker’s power to uphold India’s secular credentials in the true sense.

Why learning from Munshi’s resilience matters in Amritkaal

During Amritkaal, it becomes pertinent for Bharatiyas to instil their collective consciousness with the one civilisational truth. The truth: the people of Saurashtra, the people of Gujarat, instilled in Bharat’s history the intense fight against vehement iconoclasm, a persuasive pushback that extended generations, a cogent struggle for freedom.

Munshi’s contribution is in making us aware that the soil of Somnath witnessed two constants — the urge of the local people to protect the abode of their deity — and their faith in Somnath that drove the cycle of reconstruction. The rebuilding of the structure each time was a process in collecting civilisational resilience. The architectural geometry that arose from the rubble left by the invaders’ attacks, shaped up as an oration in the resolve to defeat the invader. Munshi mentions his belief that Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni was driven by the urge to destroy the belief of Hindus in Somnath. The concentration of Hindu belief in Somnath as the symbol of belief, was centred on the vigrah, which the Hindus saw as an effective deterrent to iconoclasm – in the protection of sacred idols in the rest of Bharat.

Somnath, thus, attracted the wrath of the iconoclast in 1025 to keep Bharat reeling under its impact in the centuries that followed. If one looks closely, Somnath would become the destination for the iconoclast’s fanatic gusto for destroying the belief that was focussed on the protection of the sacred idols not just here, but across Bharat.

Munshi made sincere efforts to arrive at some answers regarding provenance with the help of insights and nuances from archaeologist BK Thapar. His review of the parts of Somnath’s abode, particularly those faded or fading under the impact of time, those imposed and superimposed by the invaders’ conquests, those that narrated the history of ancient Gujarat, those that withstood the salt, breeze and winds from the mighty sea. The inestimable achievement of Munshi’s pursuit of Somnath’s history was his distinct scrutiny of the visible war and the invisible battles undertaken to preserve Somnath.

Munshi was able to ignite Patel’s own vision required for the conversion of the “national urge” into the final series of steps that would open the path to the reconstruction of not only Somnath, but of Bharat’s dignity, in the era of cultural resurgence brought by Independence. Munshi’s perceptive engagement with aspects related to relics, inscriptions, ceramic pottery, and devotion etched in stone, centred on Somnath, and the worship of Somnath, underlined the piercing need to make the decisive and civilisational move to defeat cultural and spiritual desecration over centuries with architectural and cultural restoration and reconstruction.

The publishing of the book had to be aligned with the “installation ceremony” of the Somnath in 1951. PM Modi is no scholar or historian. KM Munshi mentioned that he was no scholar. But just as Munshi, PM Modi understands why it was pertinent for Bharat of the past to rebuild the destroyed. Munshi makes us realise the oft-forgotten truth about Somnath. As one of the prime seats of Shaivism, one of the 12 Jyotirlingas, it was also the living symbol of freedom. Every time it was under attack, freedom was challenges and left shattered.

Who razed and destroyed, who reconstructed and rebuilt, when were the different temples built for preservation and restoration at Somnath, which outlet preceded which, and what were the different periods in which the different shrines were in use: Munshi has looked at these aspects in detail. Aspect under observations in Munshi’s own study, was the level of the different structures of the temples raised in the different periods and the use of the stones pointing to the rules under which the temples were constructed. Munshi’s expression in writing displays the realisation that the creation in stone stretched to 2,000 years of Hindu history, of Bharatiya civilisation.

The history of Somnath’s destruction and ruination over the different eras, by the different generations of iconoclasts, their continuous and consistently acerbic efforts to destroy Somnatha stood against the stubborn will of the devotees to rebuild. Each time the devotee was left stunned and crushed by the marauding and murderous attempts to annihilate the abode of their deity, the worship of Somnath and devotion backed them to absorb the wreckage, for that one task – rebuilding. The awareness of the ancient glory of Somnath, their own ancient heritage, its magnificence, was everlasting and could not be wiped out by even the mightiest of generals of the armies of iconoclasts. Munshi mentions the “throbbing zeal” in the devotee to preserve the “core” of the belief and faith. This would have been impossible without the realisation of the greatness that defined the Somnath Mandir — greatness that was collective heritage.

Munshi has been able to capture the essence of the power that helped the Hindu devotee rebuild and preserve Somnath – in the wake of multiple and targeted attacks. His reflections are of great importance. One, they give us two words of profound inspiration and value: “collective greatness”. Two: the aspect of the connection with the ancient and the past in the present. Three: the eternity of Somnath as a symbol of “faith” — Sanatan — driving the determination to restore and rebuild.

These aspects, Munshi underlines, are the reasons why the Jyotirling holds the “premier” place in the dharmic literature of Bharat. They are the reason, he writes, why after Mahabharat, the mention of “Prabhasa” does not arise with “reverence” which he finds not expressed for any other teertha in Bharat. Munshi’s observation of how the Hindu mind perceived the destruction of Somnath by the iconoclast reveals that its absorption was deep — in the subconscious — as a “national disaster”. For Munshi, the impression of Somnath being the focal point of Gujarat’s own sense of nationalism, Somnath’s destruction and the devotees’ counter-conquests — was important for Independent India.

He documented the present and wrote for the future, particularly for scholars, historians and archaeologists to use his writing for their work, with the same determination of the devotee, who defeated the concentrated attacks on Somnath for the obliteration of dharma and the dharmic by staying resilient during the previous centuries. The cry of Gujarati pride — “Jai Somnath” – inspired his writing and energies guiding his literary works towards Independence and 1947. Embedded in Hindu history, Somnath and the slogan of “Jai Somnath”, nurtured his imaginations and re-imagining of the several devotees of Somnath, who perished to protect and preserve the Shiv Linga at the temple. The desire and will to witness the “resurrection” of Somnath was multi-generational. It drove Munshi’s own understanding of Sardar Patel’s sense of freedom being incomplete without the restoration of Somnath.

It gives us the message that looking at the future was difficult for Bharatiya visionaries until they achieved restoring the dharmic, civilisational and cultural as requisite to real freedom.

The establishing of truth, the conversion to tangible

Munshi chronicled his own observations of the temple’s state in his times, the extent of devastation and wreckage left by the attacks, plunder and loot on and at Somnath in the past and history and the neglect it was suffering during his times. Inspiring him to turn around the story was the rekindling of restoration in Somnath’s history.

When the Marathas conquered Saurashtra, Somnath saw the rekindling of restoration. According to Munshi’s account, Devi Ahilya Bai Holkar found the ruins “beyond repair”. Somnath was thus installed in a new temple, at a little distance from the old site. Devi Ahilya Bai Holkar, known for her rebuilding and restoration efforts in the preservation of dharmic heritage across India, thus helped establish not only the abode for Somnath but also the basis of Bharat’s political sovereignty, of which the temple was and is the civilisational nerve centre, the throbbing core.

The foundation stone of the seventh temple was laid by Jam Saheb in May 1950. The consecration of the silver Nandi, KM Munshi points, was a moment of the shrines “resurrection” as it was set in the anniversary of the pulling down of the fifth temple. Munshi went into the garbagriha of the temple for the first time in 1950. He tried to arrive at some answers regarding provenance with the help of archaeologist BK Thapar.

Munshi has documented in detail about the different architectural components of the temple, the ruin and wreckage, the changes brought under the attacks on the ancient temple by rulers who were also destroyers, prior to 1706, the reconstruction, it quality, the repairs carried out and the material used for it, the older stones found at the temple and their locations. Munshi looked at the jigsaw of questions mysteries regarding the parts of the temple that were desecrated, inscriptions found at the site, carvings on plinth, the nature of pillars, and aspects related to Temple One, Temple Two, Three, Four and Five, including the stones used for making them. While pondering on the different hypothetical nuances, he does not part with the appetizing curiosity of a student. Signs of violence on the temple meet him in his immersive pursuit.

Archeologist BK Thapar wrote that the Somnath Temple symbolises the “racial instinct for survival”. As an excavator, Thapar seemed moved by the rhythm of creation, destruction and restoration signified in the history of Somnath. Bringing under the lens the mediaeval remains at Somnath was needed by the 20th century Bharat. It was amplified by Munshi, who was Chairman of the advisory committee of the Somnath Board of Trustees. He moved the Department of Archeology in 1950 to excavations.

For Thapar, Somnath also happened to be the representation of the evolution of architecture of Gujarat. The excavations would provide answers on the earlier temples and the material of historic importance, which were present in abundance at the site.

Munshi has compiled the subsequent desecrations and the assured if not immediate reconstruction, rebuilding, restoring counter from Hindus. Credit belongs to KM Munshi for establishing the truth, leaving no room for doubt, that under attack of the iconoclast was the ancient glory of the temple. He documents the attack made by Alaf Khan, a general of the Khilji rule, in 1297. Munshi traces the series of attacks up to the rule of Aurangzeb – 1669 being the water mark – when the Mughal ordered that the temple be demolished. According to Munshi’s account, amidst the defiance to those orders, some insertions were made by the iconoclast rulers to the structure. Devi Ahilyabai Holkar, known for her intelligence, passion for building and rebuilding for dharma and her devotion for Shiva, exhibited a fusion of strategy and architecture by layering the abode of the Linga for its concealment, to protect it from the gaze and axe of the fanatic iconoclast.

Honour, resurgence and Munshi’s “throbbing zeal” to rebuild culture

Munshi is the 20th century witness to centuries of remains that stood after a thousand years of vandalism hammered down on Somnath. He was able to take into account the span of destruction and restoration through the eyes of the Bharatiya to whom mattered the civilisational grandeur of this Centre of Hindu devotion. He viewed Somnath beyond its antiquity. He wanted to place the context of its value, preservation, restoration and rebuilding as a national project. He desired to draw away the aspect of mere historical attention it received. He wanted to shape up its civilisational and cultural recovery from the memory of destruction of the past and the neglect of the present. His present and his times. Driven by creative ideals, Munshi brings to light Sardar Patel’s own view of the Somnath Mandir. Patel recognised the pressing need for the restoration of the idol and not just efforts to increase the life of the temple through structural changes. The “honour” and “sentiment” of the Hindu mattered to Patel. Munshi indicates that considering several deliberations regarding the installing of the vigraha, and scrutiny of the existing structure, it was decided in 1947, that the temple will be rebuilt.

Munshi states that Patel, after suggestions from Gandhi, decided that the Government would not make any monetary contribution for the temple’s rebuilding. Munshi’s words reflect the crystal clear creative clarity operated within his vision for connecting the temple with “cultural resurgence”, Indology, the study of scriptures, learning, well being, and a gaushala.

He submitted his vision for an All India Sanskrit University at Prabhasa Patan to Patel. Munshi even worked out the math and stated who the probable contributors- the governments would be. Patel gave a nod. In Munshi’s own account, it is mentioned that Patel nominated the “first trustees”. Patel wrote to Jam Saheb of Nawanagar, one of the trustees, requesting him for donation for the Somnath Fund.

Nehru was lucky. He escaped, perhaps, the scale of negative public perception for his stand on the participation of Munshi and Prasad in Somnath’s building and restoration, unlike the Nawab of Junagadh after Independence. The Nawab garnered attention for executing the Instrument of Accession under which the state was declared to have acceded to the Dominion of Pakistan “against the declared wishes of an overwhelming majority of his subjects and under the influence of the agents of the Dominion of Pakistan.”

KM Munshi surpassed the human limitations of scanning history to extract the healing mantra from its ruins. He documented the one truth that must fuel our continuity as Hindus and Bharatiyas. The abode of the deity will have to be protected by the devotee. Our ancestors, Munshi suggests in his writing, believed that the iconoclast will be perished by the deity himself. That would eventually happen, but not until the devotee awakened and rose to protect his dharma, deity, and devotion.

As we move towards the next thousand years, through and towards 2047, we must remain awakened to rebuild and restore, document and discover, our own heritage. We must take the Somnath Swabhiman Parva as the beginning point to continue assisting KM Munshi, helping PM Modi, to reclaim and rebuild Hindu sacred spaces, and the Hindu idea of nation building, for Hindu honour and dignity of the unknown Hindu protector and for the known Hindu warriors. Jai Somnath.