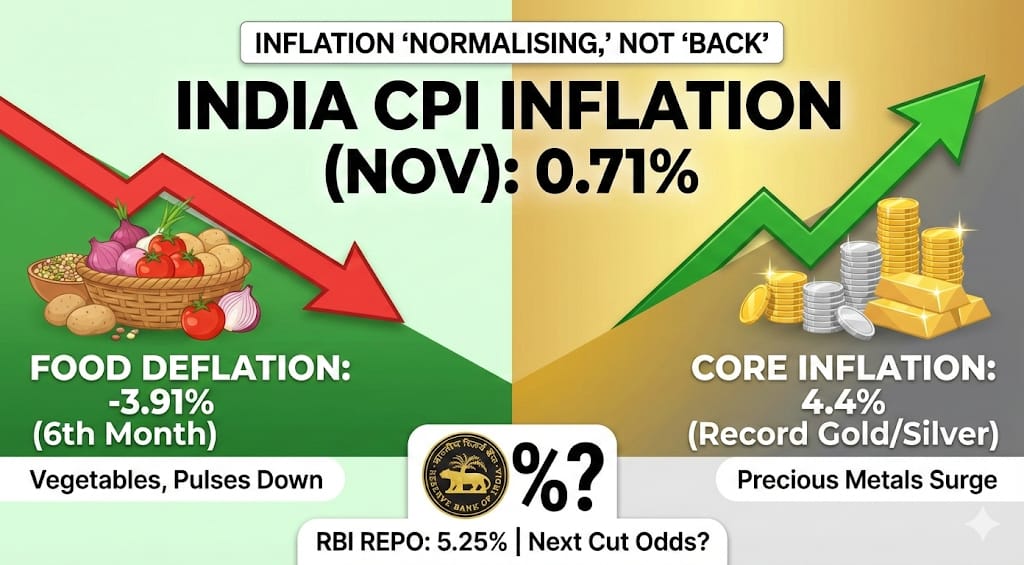

Headline inflation moved up from a record low due to base effects, while vegetables and pulses kept food inflation negative for the sixth month; record gold-silver inflation kept core near 4.4%

India’s headline retail inflation (CPI) rose to 0.71% in November from 0.25% in October, according to data released by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSP). If inflation is rising again, should households worry that prices will start climbing sharply? The clearer answer is no, not based on this number alone, because the increase looks more like a “math effect” and a change in mix than a fresh wave of broad price pressure.

Even at 0.71%, inflation is far below the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) 4% target for the tenth month in a row and below the 2% lower end of the RBI’s 2–6% comfort band for the third straight month, which is why economists are still discussing room for more rate cuts rather than emergency tightening.

The key explainer term here is “unfavourable base effect.” What does that mean in simple language? CPI inflation is measured year-on-year, so today’s price level is compared with the price level in the same month last year. If last year’s prices were unusually low (or moved in a particular way), this year’s inflation rate can look higher even when current month price changes are modest.

In November, that base effect was particularly relevant for food items, pushing the headline inflation rate up from October’s record low. So the headline number rose, but that does not automatically mean people suddenly faced a new burst of monthly price increases across the board.

Now the most striking part: food inflation stayed below zero for the sixth consecutive month, with food prices down 3.91% year-on-year in November (after -5.02% in October). How can headline inflation rise if food is still getting cheaper compared with last year? Because food deflation became less intense—moving from -5.02% to -3.91% is still negative, but it is a “smaller negative,” and that mechanically lifts the overall CPI reading.

Paras Jasrai, Economist at India Ratings & Research, quoted in The Indian Express report, explained that the marginal uptick in retail inflation was driven by the decline in the degree of food deflation, with the deflationary trend led by vegetables and pulses; he also noted cereals inflation fell to a 50-month low of 0.1% supported by a favourable Kharif sowing season. The practical takeaway is that the food story remains a disinflation story, but the tailwind from food is not as strong as it was a month earlier.

Looking inside the food basket helps explain why households may still feel mixed signals. Vegetables were 22.2% cheaper year-on-year, pulses were down 15.86%, and spices fell 2.89% in November, which is why the overall food index remained in deflation. But are prices still rising month-to-month even if they are lower than last year? In some cases, yes.

Vegetables rose 2.6% in November compared with October, pulses edged up 0.1%, and eggs recorded the largest month-on-month jump at 5.2%. Overall food prices rose 0.5% month-on-month. This is why a family can see certain weekly bills rise even when annual inflation prints look extremely soft.

The second big piece of the puzzle is core inflation, which stayed broadly steady at about 4.4% in November, according to calculations cited by The Indian Express. Why didn’t the core fall when headline inflation is near zero? The answer lies in precious metals. Gold and silver inflation hit new record highs—58.32% for gold and 65.52% for silver in November.

Even though gold and silver together carry only 1.19% weight in the 299-item CPI basket, their extreme price rise can still push the aggregate meaningfully. RBI Governor Sanjay Malhotra recently indicated that sharply higher precious metal prices may be lifting headline inflation by as much as 50 basis points, which helps explain why “underlying inflation pressures” can be low while the measured core doesn’t soften much.

What does all this mean for RBI policy after the MPC cut the repo rate by 25 bps to 5.25%? The direction of travel matters. The RBI has projected inflation will rise from these unusually low levels over coming quarters—0.6% on average in October–December, 2.9% in January–March 2026, 3.9% in April–June 2026, and 4% in July–September 2026—so the current softness is not expected to last indefinitely.

Another question is immediate: what December print would keep the RBI’s near-term path intact? To match the RBI’s 0.6% average for Q3, December inflation can rise up to 0.98%, and Jasrai expects December near 1% with food remaining “benign” in early December, as reported.

Bank of Baroda Chief Economist Madan Sabnavis, also quoted in The Indian Express, argues there is roughly an even chance of another rate cut in February because inflation is expected to move up in Q4 while GDP growth may moderate in Q3 and Q4—exactly the kind of trade-off where the RBI could still choose to support growth if inflation stays well-behaved.

The simplest way to read November, then, is this: inflation is not “back,” it is “normalising” from an exceptionally low base, while food continues to provide relief and precious metals distort the optics of core. The next decisive checkpoint is December CPI (due January 12, per the official release schedule referenced in reporting) and the MPC meeting on February 4–6, when policymakers will judge whether food remains benign, whether core finally cools once metals stabilize, and whether growth concerns warrant another cut.