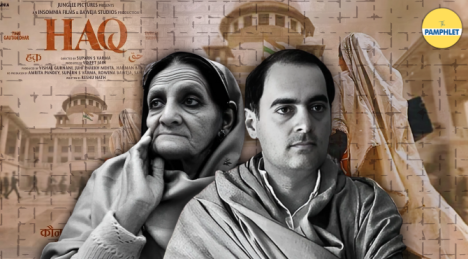

Emraan Hashmi is set to return to the silver screen, but this time not with a thriller or romance, instead with a political courtroom drama that is bound to stir debate. In November 2025, “Haq”—inspired by the landmark Shah Bano case and starring Emraan Hashmi alongside Yami Gautam—will be released in theatres.

This marks part of a growing trend in Bollywood where films are beginning to confront uncomfortable truths rather than pandering to the decades-old template of anti-Hindu, anti-India narratives. While that old current still exists, movies like The Kashmir Files, The Bengal Files, Chhava, and now hopefully, Haq will reflect a new wave of cinema that dares to hold up a mirror to society. These films question why genocides are denied, why political violence is whitewashed and why the rights of marginalized women are conveniently ignored—all in the name of being “politically correct.

From the looks of the trailer, the movie might just talk about the struggles of Shah Bano (Shazia in the film) with the judiciary, but it is essential to remember that while Shah Bano received justice from the judiciary, it was Rajiv Gandhi who passed the ultimate bill that was responsible for the pain of divorced muslim women.

Who was Shah Bano?

Shah Bano Begum’s story begins like countless others—marriage in 1932 to Mohammad Ahmed Khan, five children, decades of homemaking, and then betrayal. In 1978, after 46 years of marriage, at the age of 62, she was cast aside by her husband, who divorced her and declared that he owed her nothing beyond the iddat period—roughly three months of post-divorce maintenance.

For many women, that would have been the end: silence, shame, and survival through dependence on relatives or charity. But Shah Bano chose differently. She invoked Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), a secular law that mandates maintenance for any destitute wife, regardless of religion.

The Supreme Court verdict: A triumph of justice

In 1985, the Supreme Court delivered a decision that should have marked a turning point in India’s pursuit of gender justice. The Court ruled:

- Section 125 CrPC applies to all citizens, without exception.

- A divorced Muslim woman cannot be abandoned after iddat; her husband remains responsible for her livelihood.

- Mahr (a token dowry given at marriage) is not a substitute for maintenance.

- The Quran itself, when properly understood, supports the rights of women and does not permit their abandonment.

The judgment was crystal clear: equality before law cannot be bartered away at the altar of religious orthodoxy. For the first time, a destitute Muslim woman’s rights were affirmed not as charity, but as justice.

The backlash: Clerics vs. Constitution

The Supreme Court’s verdict should have been hailed as a milestone for gender justice. Instead, it triggered a storm of outrage. Influential clerics and Muslim personal law boards reframed the case—not as a woman’s right to maintenance, but as an attack on sharia itself.

Mosques echoed with fiery sermons, streets filled with protests, and pamphlets warned that the judgment threatened the survival of Islamic personal law. The narrative was sharpened into a communal slogan: “This is not about Shah Bano; this is about Islam.”

Thus, what began as a woman’s plea for maintenance had been cynically repackaged into a community’s battle for survival. Shah Bano was not only abandoned by her husband; she was abandoned by her own people, vilified as a pawn of Hindu courts, and condemned as a traitor to her faith.

The pressure soon turned political. Congress leaders were warned that upholding the verdict would cost them Muslim votes. Faced with organized agitation and the fear of electoral backlash, Rajiv Gandhi’s government chose appeasement over principle.

Rajiv Gandhi’s capitulation

Rajiv Gandhi, fresh from his landslide victory of 1984 with more than 400 seats in Parliament, had the mandate and the numbers to stand by the Supreme Court. Instead, he capitulated.

In 1986, the government passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act—a law that overturned the Supreme Court verdict and restricted a husband’s responsibility to the iddat period. Beyond that, a woman would have to depend on relatives or waqf boards.

The very essence of justice had been undone—not by the judiciary, but by Parliament. And it was not done out of conviction but out of fear. Congress chose the appeasement of clerics over the empowerment of women.

The message was clear: in the India of 1986, vote banks were worth more than dignity.

The lone rebel: Arif Mohammad Khan

Amidst this betrayal, one voice rose in defiance—Arif Mohammad Khan, a Muslim minister in Rajiv Gandhi’s cabinet. In a powerful speech in Parliament, he quoted the Quran itself to argue that faithful Islam could never deny women their rights.

When the government brought in the regressive 1986 law, Khan resigned. He declared that he would not be a pawn in the game of appeasement. His resignation remains one of the rare examples of political integrity in Indian politics.

However, Congress did not value integrity. It cared only for electoral arithmetic.

The Babri Masjid angle: A balancing act gone wrong

If Congress thought its troubles ended with appeasing Muslim clerics, it was wrong. The Shah Bano reversal had deeply angered Hindu society, which saw it as proof that Congress cared only for minority votes.

In a desperate attempt to “balance” this anger, the same Rajiv Gandhi government facilitated the unlocking of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in 1986, allowing Hindu worshippers entry for the first time in decades.

In a single year, Congress played both sides: betraying Muslim women to placate clerics, and then opening Babri’s locks to appease Hindus. It was a cynical political gamble, but instead of pleasing everyone, it bred distrust everywhere.

For Muslims, the Congress looked like a party that could not stand up to the majority. For Hindus, it looked like a party that would sell out the Constitution for minority votes.

The result: polarization deepened, mistrust grew, and the seeds of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement were sown.

The long aftermath

The Shah Bano betrayal did not vanish with time. It scarred India’s politics for decades.

- 2001 – Daniel Latifi Case: The Supreme Court tried to salvage justice by interpreting the 1986 law to mean that husbands must make a “reasonable and fair provision” for wives beyond iddat. In other words, the Court reasserted the spirit of the original Shah Bano judgment.

- 2019 – Triple Talaq Ban: The decisive shift came with the Modi government’s Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, which criminalized instant triple talaq. Where Congress in 1986 had surrendered to clerics, the BJP in 2019 stood firm against them, prioritizing women’s rights over vote-bank arithmetic.

The contrast could not be more apparent:

- Congress in 1986: Sacrificed justice at the altar of appeasement.

- BJP in 2019: Delivered justice despite clerical opposition.

What Congress should have done in 1986, Modi’s government finally did in 2019.

Why Shah Bano still matters

The Shah Bano case was more than a legal dispute—it was a test of India’s secularism, its Constitution, and its politics. Congress failed that test spectacularly.

It proved that its so-called “secularism” was nothing more than opportunistic vote-banking. It appeased clerics while betraying women. It pleased no one, but it divided everyone.

And in doing so, Congress did not just abandon one older woman—it reshaped Indian politics. Its duplicity created the vacuum into which the BJP stepped, armed with the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and a promise of unapologetic politics.

Conclusion

As “Haq” releases in November 2025, audiences will watch a courtroom drama about one woman’s fight for justice. But beyond the film lies the unvarnished truth—that Shah Bano’s fight was betrayed not by her husband, not by her community alone, but by the Indian National Congress.

In 1986, Congress proved that it valued votes over rights, expediency over principle, and compromise over the Constitution. It silenced the judiciary, betrayed women, and played a double game with communities—all in the name of power.

Today, when the party lectures about protecting the Constitution, it must be reminded of the day it shredded the very spirit of constitutional justice for electoral gain.

The question remains the same as it was in 1986:

When justice and votes collide, which will you choose—Constitution or compromise?

For Shah Bano, the answer was compromise. For India, the consequences were historic. For Congress, the shame is eternal.