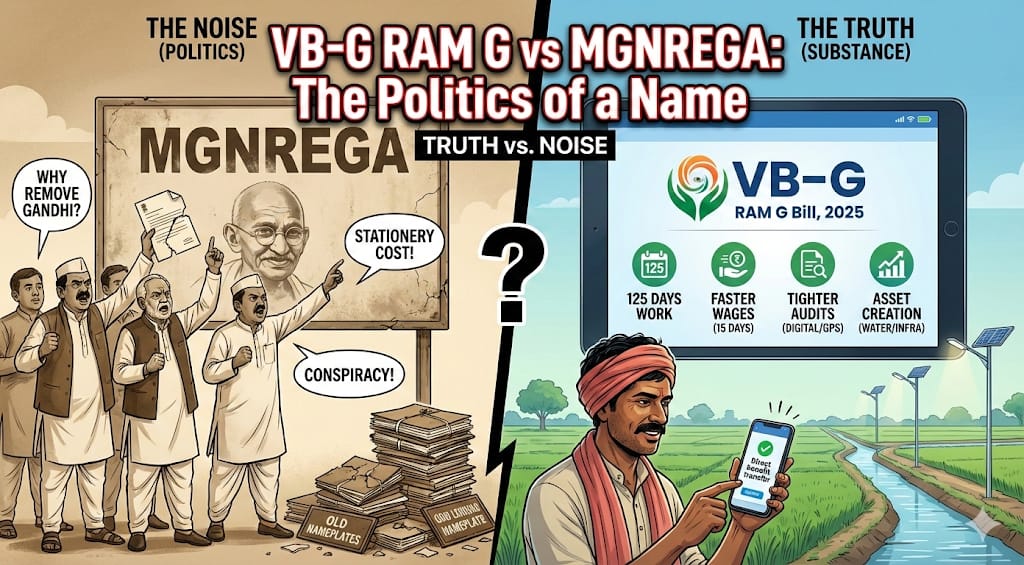

The Centre bringing VB–G RAM G Bill, 2025 to replace MGNREGA should have triggered one basic discussion: will the rural worker get more work, quicker wages, and less corruption? Instead, the loudest noise is about a nameplate. That’s the part that feels like pure political habit—because it’s easier to sell outrage about “branding” than to read what the law is actually promising. If a scheme moves from 100 to 125 guaranteed days, who exactly loses? If payments are meant to land within a week or 15 days of completing work, who exactly is being harmed? And if unemployment allowance is written in for delays or denial, how is that “ending” the right to work?

The Opposition’s script goes like this: “They are removing Mahatma Gandhi’s name, so their intention must be bad.” But intention is not proven by guesswork; it’s proven by provisions. If the government truly wanted to wipe out Bapu’s legacy, wouldn’t the simplest trick be to keep the famous name and quietly weaken the guarantee? Yet the draft being discussed does the opposite on paper—higher days, time-bound wages, clearer work categories, and stronger enforcement tools. So the more honest question is: is this really about respecting Gandhi, or about guarding a political trophy from 2005? Because rural India doesn’t survive on symbolism; it survives on pay slips, work availability, and complaint systems that actually work.

So, the government brings a new rural jobs Bill with a bigger guarantee, quicker payments, digital tracking, and local planning—and the nation’s big debate turns out to be about stationery costs. Welcome to Indian politics. VB–G RAM G, the Viksit Bharat Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Grameen), is replacing MGNREGA, and it’s not about killing guaranteed work—it’s about strengthening it. One would imagine the Opposition would celebrate a rural guarantee going from 100 days to 125, but instead we hear Priyanka Gandhi asking, “Why remove Mahatma Gandhi’s name?” The obvious reply would be—does the name create employment, or do the provisions? If the work guarantee, allowances, transparency, and grievance system are being strengthened, then what part of Bapu’s ideals is being “removed”? Gandhi stood for self-reliance and dignity of labour. Isn’t that exactly what the government claims this new mission will restore?

You have to smile at the selective outrage. Mallikarjun Kharge has called this a “BJP-RSS conspiracy” to end MGNREGA. A conspiracy? Against whom—against rural workers getting 25 more days of paid work? He says Gandhi’s name is being erased. But if the same party that garlands Gandhi on October 2, builds museums on his life, funds Sabarmati’s restoration, and campaigns on his idea of “Gram Swaraj”, really wanted to erase him, would they bother expanding a rural job guarantee in his name’s spirit? What’s next—will the Opposition say that increasing village employment dishonours Gandhi because it doesn’t carry his face on a logo?

Then comes Priyanka Gandhi’s masterpiece argument: “Whenever names change, a lot of stationery and signage cost is wasted.” That’s true—there will be new nameplates and letterheads. But what costs more, really—printing new forms, or losing ₹193 crore in fake job rolls and irregularities, as reported under the older setup? This new VB–G RAM G framework talks about GPS-tagging of works, biometric attendance, mobile monitoring, AI-based fraud detection, and social audits twice a year. Maybe that’s what hurts political comfort zones more than the “stationery bill.” Because digital sunlight makes ghost workers vanish, and transparency reduces the middlemen who thrived under the old loopholes.

Jairam Ramesh says Modi sarkar loves changing names and packaging. But here’s the question—if the government were only rebranding, why bother changing the entire legal framework, the cost-sharing model, and the work architecture? Under the VB–G RAM G plan, work will now focus on four thematic areas—water security, rural infrastructure, livelihood development, and disaster resilience. That means jobs will leave behind assets. Instead of digging pits every year for the sake of showing “work done” on paper, village labour will help build what strengthens agriculture and income permanently. That sounds a little more substantive than “packaging.”

And Akhilesh Yadav—well, he calls every reform “politics of distraction.” But here’s the real distraction: the Opposition keeps fighting over a label while rural India needs better leak-proof pipelines of money. The new Bill fixes wage payment delays by setting a two-week timeline. It introduces unemployment allowance if work isn’t provided. Its very foundation is scheduled, digitally tracked payments. So what’s the Opposition really objecting to—that the poor might now get paid on time?

So what is actually changing, beyond the label? The proposed Bill raises the guaranteed employment from 100 to 125 days per rural household per financial year, and it promises payments within a week or 15days of work completion, with an unemployment allowance if deadlines aren’t met. Ask a direct question inside the village economy—“What hurts more: a renamed scheme, or delayed wages?”—and the answer is obvious. The Bill also classifies work into four categories—water security, rural infrastructure, livelihood infrastructure, and disaster resilience—so the programme is not just a wage channel but an asset-building engine. If the goal is to convert public works into durable productivity, then this is not cosmetic change; it is the state attempting to buy tomorrow’s resilience with today’s labour.

The loudest criticism is symbolic: “Why remove Mahatma Gandhi’s name?” and “Is the government uncomfortable with Bapu?” But the counter-question writes itself: if a government wanted to erase Gandhi, would it keep “Bapu” in the political and administrative vocabulary at all, or would it increase the statutory guarantee and tighten the rights framework? The Bill does not read like demolition by stealth; it reads like a reframe—from an entitlement-first safety net designed for 2005 conditions to a mission-style rural development architecture aligned with Viksit Bharat 2047. The Opposition’s assumption seems to be that any renaming equals disrespect, but that logic collapses when you see the text pushing stronger timelines, greater days, and defined asset outcomes. Respecting Gandhi is not a naming ritual; it is ensuring the poorest citizen does not get cheated out of wages.

Another flashpoint is the “no work during peak agricultural season” provision, often described as denial of employment. But ask the practical question: “If farm sowing and harvesting are underway, do rural workers have fewer options or more?” Typically, peak season pulls labour into better-paying farm work, and public works competing at that time can create labour shortages, wage spikes, and cost pressures that eventually feed into food prices. The Bill’s reported 60-day stoppage window isn’t a continuous lockout; it is designed to avoid clashes with agriculture’s busiest weeks. In plain terms, it tries to protect farmers from labour scarcity and workers from being forced into a lower-paying public works schedule when the farm economy is paying more. Balance is not denial, and aligning job schemes with farm cycles is not anti-poor—it can be pro-income if implemented honestly.

Then comes the cost-sharing outrage: under MGNREGA, the Centre covered 100% of unskilled wages, while the new model proposes a 60:40Centre–State funding split (and 90:10 for North-East and Himalayan states, 100% for UTs), with an annual outlay stated around Rs 1.51 lakh crore and the Centre contributing about Rs 95,692 crore. The question critics should answer is: “Is shared funding abandonment, or shared accountability?” India runs many schemes on standard sharing patterns, and when states have skin in the game, implementation pressure can rise rather than fall—provided the Centre’s releases remain timely and transparent.

If the Opposition wants a serious debate, it should debate safeguards on fund flow and performance, not assume that every redesign is a retreat.The reform’s most consequential pivot may be transparency and monitoring: Aadhaar-linked verification, biometrics, geotagging, GPS and mobile monitoring, real-time dashboards, AI-based fraud detection, weekly disclosures, and mandatory social audits twice a year.

Critics call this surveillance; supporters call it wage protection. Ask the worker: “Would you rather have a system that ‘trusts’ middlemen, or one that makes wage theft harder?” Digitisation is not a moral virtue by itself, but in a scheme historically vulnerable to fake muster rolls, ghost works, and delayed payments, the promise of stronger verification is not authoritarian—it is a design choice to reduce leakage.

Finally, the political charge that the government is obsessed with rebranding deserves a grounded response: yes, renaming has costs—files, signage, stationery—but the real waste is when Parliament and public debate obsess over labels while the rural labourer waits for money. If the Opposition believes the Bill hides dilution, its best move is not melodrama; it is demanding strict payment timelines, independent audits, and legal clarity on unemployment allowance, and pushing the Bill to a Standing Committee for scrutiny. But if the law preserves the right to work, expands guaranteed days, and tightens enforcement, then the outrage about a name starts to look less like guardianship of Gandhi and more like guardianship of a political talking point.