Dhurandhar – the film that flatly refuses to bow to the “Aman Ki Asha” narrative. The film lands like a cinematic sledgehammer, shattering the romanticised illusions surrounding our western neighbour. More than an espionage thriller, it is an unapologetic, visceral descent into the heart of a terror ecosystem. What sets it apart is its refusal to dilute reality, there is no false equivalence, no moral hedging. The enemy is shown not as a misunderstood victim, but as a decaying, venomous machinery. The applause it earns is not just for craft, but for the rare courage to tell this story without filters.

The myth of the Islamic monolith

One of the most striking aspects of the film, and the geopolitical reality it represents, is the shattering of the “Muslim Ummah” myth. As Dhurandhar takes us through the blood-soaked streets of Lyari and Karachi, we are exposed to the deep, tectonic fault lines that define Pakistani society.

To the uninitiated Indian eye, the neighbour often appears as a single green block. The reality, however, is a chaotic jigsaw of hatred. There are profound divisions: Sunnis against Shias, Punjabis against Balochs, Pashtuns against Muhajirs. In Balochistan, the state machinery crushes local dissent with brutal force; in the streets of Karachi, gang wars run on ethnic lines between the Baloch and the Pashtun. The Deobandis despise the Barelvis, and the Ahamadiyyas are hunted by all. They slaughter each other in mosques and markets with a ferocity that defies logic, driven by tribal loyalties and sectarian puritanism.

The ‘Kafir’ glue: United by hate

However, the movie subtly underlines a chilling paradox that every Indian must understand. Despite this internal fratricide, despite the Pashtun hating the Punjabi or the Sunni loathing the Shia, there is one glue that binds them instantaneously: Hatred for the Kafir. This animosity is not reserved solely for the Hindu idolater but extends with equal vitriol to Jews and other “non-believers.”

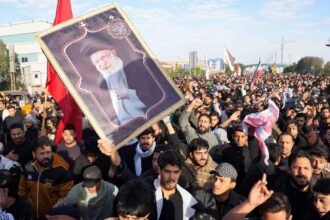

The Baloch gangster and the Punjabi General may want each other dead, but they will stand shoulder-to-shoulder when the target is the “common enemy.” This macabre unity was perhaps most terrifyingly visible during the 26/11 Mumbai massacre. As the Taj burned and Nariman House was targeted to hunt down Hindus and Jews, the usual factional fault lines across the border evaporated.

Reports from that time suggest a disturbing reality: Diverse communities, who would usually be at each other’s throats, sat glued to their screens, collectively cheering the slaughter of Hindus, Jews, and tourists. The theological programming that designates these groups as the ultimate “other” is so deep-seated that it overrides centuries of tribal warfare. In their worldview, internal squabbles are family matters; the war against the Yahood-o-Hunud (Jews and Hindus) is a divine duty. They may be divided in peace, but they are terrifyingly united in their hate for us.

The Hindu paradox: Divided we fall

Tragically, when we turn the mirror toward Bharat, the reflection is inverted. We are a civilization under siege, yet we act as if we are on a permanent holiday from history. While our enemies unite despite their differences to destroy us, Hindus remain fragmented despite a shared heritage that spans millennia.

The forces that wish to see Bharat perish, both internal and external, have successfully weaponized our diversity against us. They keep the pot of caste divisions boiling, pitting Jat against non-Jat, Dalit against Savarna, North against South. While the enemy consolidates under a religious identity to wage war, we are busy deconstructing our identity into smaller, weaker fragments. A Hindu in Bengal bleeds, and a Hindu in Maharashtra looks away; a temple is desecrated in the South, and the North remains indifferent.

The cost of amnesia

Dhurandhar is not merely a film; it is a frantic alarm bell ringing in a sleeping house. It exposes a chilling asymmetry that defines our times: our adversary possesses an existential clarity about their goal, our annihilation, while we suffer from a suicidal complacency, treating our survival as a guaranteed inheritance rather than a daily struggle.

They may be rotting from within, but their decay only fuels their desperate unity against the ‘Kafir’. Meanwhile, the fault lines we nurture, caste, region, language, are not just domestic disagreements; they are the very breaches through which the enemy enters. History is littered with civilizations that perished not because they lacked strength, but because they lacked unity in the face of a focused barbarian. The enemy knows exactly who we are and what they want to do to us. The tragedy of our generation would be if we perish while still debating who we are.

Written by Rohini AV