As the Indian National Congress celebrates its 140th foundation day on Sunday, 28 December, public discourse once again revisits its central place in India’s freedom movement. That historical role is uncontested. What remains far less examined, however, is the party’s post-Independence institutional trajectory.

When viewed over seven decades, the Congress story after 1947 is not primarily about electoral defeat or ideological displacement. It is about organisational inability to retain leadership, accommodate internal plurality, and sustain governance over time.

No other political organisation in independent India has produced as many breakaway parties, splinter factions, regional alternatives, and leader-led exits across every decade, every region, and every ideological spectrum. This pattern is not incidental. It is structural.

From Movement to Organisation: The first structural shift

The Congress that led India’s freedom struggle was a coalition of several interest groups, not a tightly governed party. It absorbed conservatives and radicals, regional leaders and national figures, precisely because the freedom movement allowed ideological disagreement under a unifying purpose.

Independence ended that equilibrium. Almost immediately, the party began losing the senior leaders through their exit:

Subhas Chandra Bose, a twice-elected Congress President with unparalleled mass legitimacy, was forced out in 1939, and his subsequent formation of the Forward Bloc set an early precedent that popular mandate did not ensure organisational space within the party. This pattern continued after Independence: Acharya J.B. Kripalani, who led the Congress at the moment of freedom, departed within four years to establish the Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party in 1951, while Tanguturi Prakasam, a towering southern leader, exited in the same year.

By the mid-1950s, C. Rajagopalachari one of the era’s most respected statesmen and intellectuals also broke away, later providing ideological leadership to the Swatantra Party, reinforcing the theme of attrition among the party’s most prominent figures.

These early exits are often explained individually. Taken together, they point to something systemic: the transition from collective leadership to centralised authority was neither smooth nor consensual.

The 1960s: Fragmentation becomes normalised

The 1960s transformed Congress from a dominant national platform into a political exit route. As regional aspirations intensified, Congress responded by tightening central authority rather than decentralising decision-making. This period saw the emergence of multiple regional formations born directly out of Congress:

The formation of the Kerala Congress in 1964 institutionalised permanent factionalism within the party, setting a precedent for repeated splits. This trend intensified between 1966 – 67, with the emergence of the Orissa Jana Congress, Bangla Congress, Vishal Haryana Party, and the Bharatiya Kranti Dal, all reflecting growing regional and ideological discontent. In Uttar Pradesh, Charan Singh’s exit proved especially consequential, permanently alienating the Congress from its agrarian support base. Meanwhile, the creation of the Manipur People’s Party in 1968 signalled an early erosion of Congress influence in the Northeast, foreshadowing a wider regional decline.

Their departure indicates a party increasingly unable to contain political ambition unless it is centrally mediated. This phase culminated in 1969, when Congress split nationally into Congress (R) and Congress (O). While Indira Gandhi prevailed politically, the institution itself fractured beyond repair. From this point onward, splits were no longer aberrations but became routine outcomes.

Centralisation and its long-term effects (1970s–80s)

Post-1969, the Congress increasingly relied on centralised authority as a stabilising mechanism. In the short term, this ensured control. In the long term, it produced predictable consequences. From the 1970s through the 1980s, Congress witnessed a steady stream of departures:

Biju Patnaik’s break with the Congress led to the formation of the Utkal Congress in Odisha, while in Telangana, long-neglected regional aspirations gave rise to the Telangana Praja Samithi. The aftermath of the Emergency also triggered the creation of the Congress for Democracy, reflecting internal dissent against authoritarian centralisation. Over time, prominent leaders such as Devraj Urs, Sharad Pawar, Jagjivan Ram, A.K. Antony and Pranab Mukherjee either led or aligned with various splinter groups, underscoring a recurring pattern of fragmentation driven by unresolved regional, ideological and organisational tensions within the party.

These exits spanned ideology, caste, region, and generation. What unified them was not doctrine, but grievance: absence of internal consultation and concentration of power at the top. By the late 1980s, Congress had ceased to function as a stable umbrella. It had become an organisation where long-term political growth increasingly required stepping outside it.

The 1990s: Congress as the incubator of rivals

The cumulative effects of decades of fragmentation became starkly visible in the 1990s, when some of India’s most influential regional parties emerged directly from the Congress’s internal disintegration. These included the Tamil Maanila Congress (G.K. Moopanar), the All India Trinamool Congress (Mamata Banerjee), the Nationalist Congress Party (Sharad Pawar, P.A. Sangma, Tariq Anwar), and the PDP in Jammu & Kashmir (Mufti Mohammad Sayeed).

Alongside these major breakaways were dozens of state and sub-state level fractures across Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Bihar, Goa, Himachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur and Maharashtra, many of which retained the word ‘Congress’ in their names, highlighting the party’s inability to even preserve its own organisational brand. Collectively, this trajectory signalled a decisive shift: the Congress was no longer losing leaders over ideology, but over political viability.

The 21st Century: From fragmentation to hollowing

In the 21st century, departures from the Congress began to reflect not ideological rifts but deep institutional fatigue. Leaders such as Ajit Jogi in Chhattisgarh, Captain Amarinder Singh in Punjab, and Ghulam Nabi Azad in Jammu & Kashmir exited amid growing disenchantment with the party’s internal functioning. Among these, Azad’s resignation letter was particularly striking for its candour, as he pointed to the breakdown of consultative processes, the marginalisation of senior leadership, and a decision-making structure dominated by a small, unelected coterie rather than institutional norms.

Electoral evidence: What the data shows

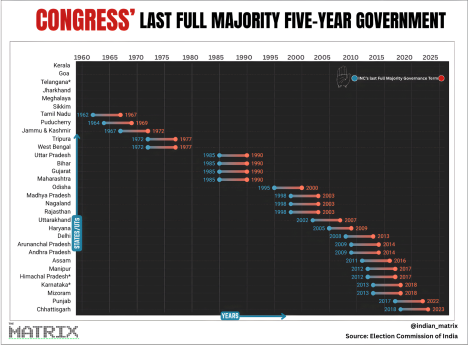

The organisational collapse is reflected directly in Congress’s governance record. As documented by @indian_matrixon on X, Congress has not completed a single ten-year consecutive majority tenure in any Indian state since 2010. In fact, in many states, such a tenure has either not occurred since the 1960s–70s or has never occurred at all.

Key findings from the data:

States including Kerala, Punjab, Haryana, Telangana, Goa, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim and Meghalaya have never witnessed two full consecutive Congress majority terms.Where longer tenures did occur, they belong to an earlier political era: Tamil Nadu and West Bengal (1957-67), Assam and Jammu & Kashmir (ending by 1972), and Himachal Pradesh and Tripura (ending by 1977).

The Congress strongholds followed a similar trajectory later. Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Rajasthan and Odisha last saw uninterrupted Congress rule during 1980–90, while Karnataka’s final extended tenure ended in 1983. By the 1990s, even this capacity faded, with Madhya Pradesh and Nagaland (1993–2003) marking the last such runs. The last instances of ten-year consecutive Congress governance, Delhi (2003-13) under Sheila Dikshit and undivided Andhra Pradesh (2004-24) under Y.S. Rajasekhara Reddy, ended over a decade ago, with no institutional replication since.

Even five-year completed majority mandates have become increasingly rare, concentrated largely in the 2000s and early 2010s, and often dependent on individual leaders rather than institutional depth.

Kerala, Goa, Sikkim, Meghalaya, Jharkhand and Telangana have never experienced a complete Congress majority government. In Telangana, the party secured its first such mandate only in 2023, with the term scheduled to end in 2028. In other regions, Congress majorities belong largely to the past. Tamil Nadu’s final term ended in 1967, Puducherry’s in 1969, Jammu & Kashmir’s in 1972, and West Bengal and Tripura’s in 1977. Former strongholds such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra and Gujarat last saw Congress complete a full term during the mid-to-late 1980s.

The early 2000s produced isolated recoveries, Uttarakhand (2002-07), Delhi (2008-13), Arunachal Pradesh (2009-14) and Andhra Pradesh (2009-14), none of which translated into sustained continuity. In the 2010s, completed Congress majorities were limited to Assam,

Manipur, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Mizoram, Punjab and Chhattisgarh, typically without a second consecutive term.

The empirical conclusion is unavoidable: Where strong leaders existed, Congress survived temporarily. Where institutional strength was required, it failed consistently.

Conclusion: A movement remembered, not an institution sustained

Congress’s historical role in India’s freedom struggle is undeniable. Its post-independence institutional record is equally undeniable.

Over seven decades, the Congress has displayed a consistent pattern: It struggles to retain autonomous leaders, struggles to absorb internal diversity, and struggles to sustain governance beyond single cycles.

The result is visible not only in election outcomes, but in the party’s long record of splits, exits, and successor formations.

On its 140th foundation day, the more meaningful reflection may not be about where Congress began, but about why a party that once accommodated the entire national spectrum now finds it so difficult to hold even its own leadership together.

This article has been coauthored by Diksha Bohra: @Diksha20o1 and Maitreyaei Upadhyay: @Maitreyaei_speaks Diksha and Maitreyaei are public policy consultants interested in geopolitics, international relations and national policy making.