The Reserve Bank of India recently issued a report titled “State Finances: A Study of Budgets 2023–24.” With the report, the central bank has sent a clear alarm to all states. According to the report, “High levels of debt come in the way of investment and growth, and states must now follow the Centre by framing a clear, transparent, time‑bound glide path to reduce their debt.”

The real danger is that as states borrow more, a growing share of their money goes to interest payments, leaving less for roads, power, schools, and jobs, which in turn slows down economic growth and hits the common man the hardest.

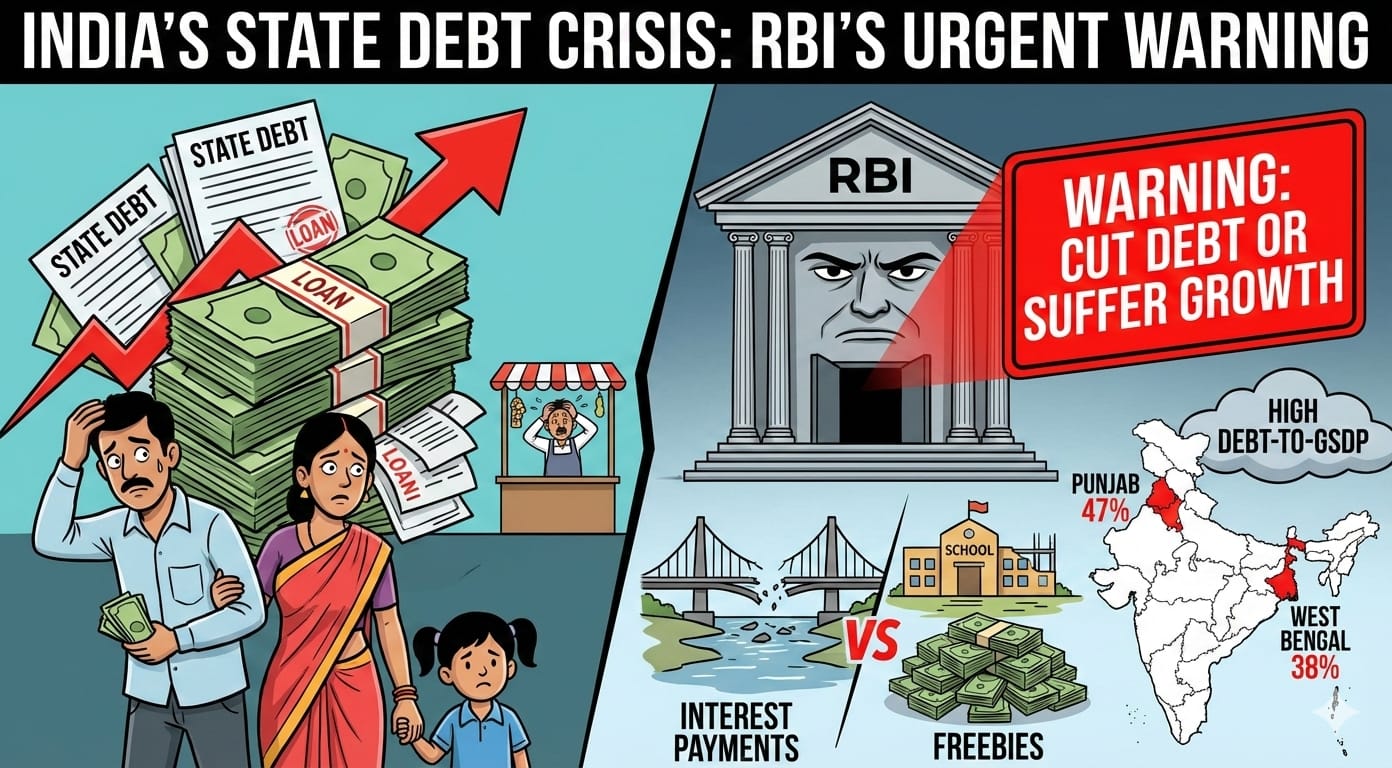

The percentage of GSDP that this debt represents is the debt-to-GSDP ratio, and this number tells us how much of a state’s income is already committed to repaying past loans. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issued a clear warning to all states: if they don’t bring down this ratio, high debt will choke investment, slow down growth, and hurt the common man’s future.

By end-March 2024, the combined debt of all Indian states stood at 28.1% of India’s total GDP, down from a peak of 31% in March 2021, mainly because of strong economic growth after the pandemic. But the RBI warns that this will rise again to 29.2% by the end of the current fiscal year, and the real trouble is not in the national average, but in the big gap among the states. Disaggregated data shows that individual states’ debt-to-GSDP ratios range from about 17.8% to as high as 46.3% by end-March 2026, with several states crossing the 30% mark. The fiscal rules suggest that states should aim to keep their debt within 20% of GSDP as a long-term target, but many are now far above this safe zone.

Among the most stressed states, Punjab stands out with a debt-to-GSDP ratio estimated at around 46–47% for 2025–26, one of the highest in the country.

Since 2005, Punjab’s debt has fluctuated, coming down from extreme levels like 62% of GSDP in the mid-2000s, touching about 39.8% in 2020, but then rising again to nearly 47% of GSDP in recent years.

This high debt is accompanied by weak tax revenue, heavy reliance on central transfers, and a large share of spending going to salaries, pensions, and interest, leaving little room for building new roads, power plants, or industries that can create jobs and boost growth.

Another big state under close watch is West Bengal, where total debt is projected to cross ₹8 lakh crore by 2025–26, with the state’s debt-to-GSDP ratio around 38%. In the last 1–1.5 years alone, West Bengal has resorted to very heavy market borrowing, taking loans of around ₹29,000 crore in one quarter and planning to borrow about ₹1 lakh crore in a single year from the market through bonds.

This is creating a classic “debt trap” pattern: higher borrowing leads to higher interest payments, and higher interest payments eat up more of the state’s revenue, forcing it to cut back on productive capital spending and instead keep spending mostly on salaries, pensions, and interest.

RBI’s deeper worry is that high general government debt (Centre plus states together as a percent of GDP) is a key weakness pointed out by global rating agencies, and it directly hurts the economy’s health.

When a state spends a large chunk of its income just on interest, its “debt-service ratio” (interest payments as a share of revenue receipts) rises, and states with a ratio above 15% are found to have capital expenditure below 2% of GSDP, compared to the all-India average of about 2.7%. This means less money is left for roads, power, ports, schools, and hospitals, which in turn slows down medium-term growth and reduces job creation for the youth.

The RBI is now pushing states to follow the Centre’s example by framing a clear, transparent, and time-bound “glide path” for debt consolidation. Just like the Centre has started targeting a reduction in its debt-to-GDP ratio (aiming to bring it down from about 56% in 2024–25 to 50% by 2030–31), heavily leveraged states should also set similar targets: for example, how much debt they will reduce each year, and how much fiscal deficit they will allow so that the debt burden does not keep rising indefinitely. Without such a glide path, states will keep borrowing more and more, and the cost of borrowing will keep rising, especially if market demand for long-term government bonds weakens.

States’ revenues come from several sources: own taxes like GST share, VAT, electricity duty, stamp duty, excise, and land revenue; transfers from the Centre in the form of tax devolution and grants; non-tax income like power charges, mining royalties, and user fees; and borrowing.

The Centre collects big taxes like income tax, corporate tax, GST, customs, and excise, and then shares about 41–42% of its divisible taxes with states, plus gives them special-purpose grants and loans. States, in turn, rely heavily on these central transfers and on market borrowing, especially when they want to spend more than their regular income allows.

A healthy budget would set aside a share for salaries, pensions, interest, and administration (the routine work), another big chunk for building roads, power, water, schools, and industries (capital expenditure), and the rest for welfare, health, education, and targeted subsidies. But RBI finds that when debt is too high, the interest burden forces states to cut back on capital spending, which then hurts long-term growth and infrastructure development.

It also warns that while social welfare schemes like free electricity and direct cash transfers to women are important in a country with deep economic divides, unchecked welfare spending can crowd out critical investments in physical and social infrastructure, so each scheme must be evaluated for its real impact and effectiveness.

The RBI’s underlying message is simple: if both Centre and states keep piling up debt and pushing spending without a clear plan, the economy will find itself in a situation where most of the government’s income is eaten up by interest and routine expenses, leaving little for new factories, better roads, and good jobs.

That is the path some economists describe as “India becoming a Venezuela of the East” — a country stuck in high inflation, low growth, and a government that keeps borrowing just to survive, not to grow. To avoid this, states must focus on fiscal reforms, improve tax collection, reduce wasteful subsidies, and spend more wisely so that the economy itself becomes stronger and the debt burden becomes manageable over time.